The rapid loss of coral reefs is both heartbreaking and personal for me. I cannot visualize the future of coral reefs without feeling a tug of despair.

In January, I wrote about the heat wave that has devastated coral reefs in my home state of Hawaii since last year. Temperatures somewhat subsided in Hawaii over the winter, but summer has hit the Southern Hemisphere hard. What is now being called the 2014-2016 global bleaching event – the third and longest such event ever recorded – is taking a breathtaking toll around the world.

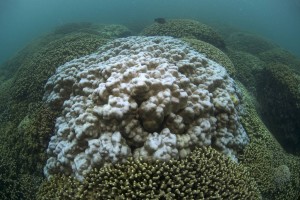

High temperatures cause the tiny pigmented algae that live within coral to exodus, leaving the coral without the energy their symbiotic algae normally provide. The coral turn the bright bleach-white color that gives the phenomenon its name. Bleached coral can recuperate from starvation if temperatures fall. But when temperatures rise and stay high for weeks on end, as they did this summer, corals’ energy stores can run out, and they die. On the northern section of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, considered one of the seven natural wonders of the world, the recent heat wave has bleached 95% of corals.

Climate change is forcing corals to live at higher and higher temperatures, and it seems that their natural adaptive processes simply cannot keep up. This has dire implications for marine ecosystems: corals are what ecologists call keystone species, meaning they are essential to the stability of the entire ecosystem in which they live. In losing corals, we also lose coral reefs, and the multitude of organisms that thrive only in the complex environment corals create.

It is not reef ecology alone that feels so bleak. The same kind of pessimism – or realism, depending on your perspective – applies to much of climate science. Retreating glaciers, shrinking forests, and rising oceans have become commonplace ideas, but if we stop to think, or spend our lives studying what these changes really mean, the issues can start to feel hopeless. Even worse than the grim forecast is the lack of clear path forward. There is no guarantee that dedicating a few dollars, or a year, or even a lifetime to this cause will do anything to change processes that were set in motion long before we were born.

Bennett, a fellow PCUR, asked me how I can care so much about corals when their future, given the recent headlines, seems so dark. “How can you work on reefs with this constantly weighing on you?” he asked.

It does weigh on me. But how could I not?

Last summer, my mentor’s lab group at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution tracked coral bleaching as a heat wave swept over Dongsha Atoll in the South China Sea. Off the coast of the tiny, uninhabited atoll, they surveyed miles of bleached reef, returning with photographs of bleached and dead corals. Some of the dead corals were huge, probably hundreds of years old.

My adviser, Anne – a vibrantly passionate person under all circumstances – found energy in the tragedy, not despair.

The visual evidence was staggering, and our lab group of coral-lovers was appalled. But my adviser, Anne – a vibrantly passionate person under all circumstances – found energy in the tragedy, not despair.

“How can we tell this to people so they listen?” Anne asked. She pointed at a picture of a looming Porites coral on Dongsha, dead and overgrown with filamentous algae. “This coral lived through World War II. It lived through the American Revolution, and through every other bleaching event we’ve seen. But it didn’t make it through 2015.”

She checked the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Pacific bleaching watch every morning, coming into the lab alight with intensity. “Did you see the bleaching watch?” she’d ask everyone in the office. “We have to get out to the Pacific and monitor this.”

She was focused on the next steps for the science: funding, carrying out, and communicating research; understanding how some corals and reefs survive the effects of climate change; using this knowledge to help protect corals in the future.

In Anne, and in the professors I know best at Princeton, optimism and action go hand-in-hand. We are faced, perhaps, by a choice. We can give up on the field and live out our lives, letting the earth roll on towards its fate. Or we can choose a mission, however small or large; choose to believe in the possibility of success, and choose to give this effort everything we have.

Will my children and grandchildren know what it’s like to swim on a coral reef? Will they watch young wrasses darting in and out of the rocks, peer into the heart of a cauliflower coral and see the eyes of a speckled crab peering back?

I’m not sure. But I do know that, no matter how grim the forecast, despair doesn’t help. Things are bad, and things are changing, but there is hope. There is enough hope – for me, at least – that it is worth caring, worth turning fear into the fuel of passion. This challenge is worth everything we have.

— Zoe Sims, Natural Sciences Correspondent