In an ideal world, research is pretty straightforward. Evidence is collected, synthesized, and analyzed. Meaning emerges. Results point to objective truth.

But if there’s anything I’ve learned from the first two weeks of ANT 301 (The Ethnographer’s Craft), it’s that research is often far from this ideal. Ethnography, at its core, is a subjective science. But that does not discount its intellectual value.

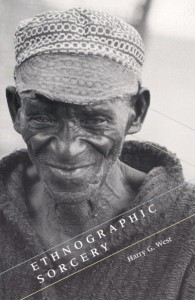

We recently read Harry G. West’s Ethnographic Sorcery, an account of West’s research in Mueda, Mozambique, where he studied sorcery as a prominent belief system. In short, Muedans believe that there are sorcerers among them who turn into lions and claim innocent lives. Early in the book, West recounts a conference he held to bounce his ideas off of community members. There, he presented a theory: we may understand these lion-people as metaphors for power play in society. An awkward hush took over the room before a schoolteacher spoke up. “I think you misunderstand,” he said. “These lions that you talk about … they aren’t symbols — they’re real.”

The case of the lion-people as metaphors reveals a problem of subjectivity: interpretations are often based on vastly distinct epistemologies, or ways of understanding the world. West acknowledges that calling lion-people metaphors is a fallacy because it dismisses local belief systems. In other words, viewing aspects of other cultures as metaphors rather than truth is a way of holding Western values above others.

It’s a good example of how anthropology is, inherently, an interpretive science. This is not to take away from the immense value of anthropological research, but rather to highlight its subjective nature. West plants the idea that anthropologists themselves are sorcerers, shaping and twisting the people they study into presentable research topics.

As we discussed in class, this molding of local experiences into coherent ethnographic writing manifests itself at every step of the research process. Preliminary readings, for instance, ground research in existing academic discourse and debates, but also place artificial boundaries around a project. This carries over to the field, where we often misinterpret and wrongly ascribe importance to certain happenings. And later, during the writing process, we are prone to other issues of subjectivity as we determine how to analyze honestly, present our subjects respectfully, and insert ourselves into the writing. Ultimately, the product is a crafted piece of academic writing that fuses elements of science and memoir.

Again, calling anthropology a subjective science is not to detract from its worth — quite the opposite. It may illuminate aspects of the human condition by using personal experiences as a lens for acquainting ourselves with others. Ethnography, as such, is as much an analysis of the ethnographer as one of the community studied. While we must remember that these writings are highly curated, we can still appreciate how ethnography gets at the subtleties of individual condition in a way that other methods cannot.

Concerns about subjectivity extend beyond the social sciences and across disciplines. People are people, and since it is impossible to eliminate subjectivity in research, we must acknowledge and embrace it. In that way, research, ethnographic or otherwise, parallels the human experience — it is rarely cut and dry.

– Dylan Blau Edelstein, Humanities Correspondent