When you’re struggling to begin a paper, perhaps the last thing on your mind is the possibility that you might have too much to write about. But sometimes when you’re struggling to start, it’s not because you don’t have enough to write about, but because you have too much. Have you ever found yourself with so many competing ideas bouncing around in your head, each clamoring for expression, to the point that your writing has no focus?

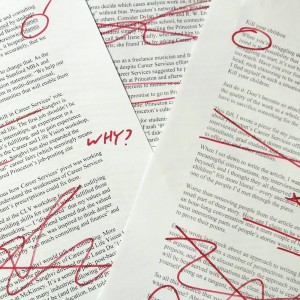

When I find myself in such a situation, I remember an unfortunately violent piece of editing advice: Kill your children — that is, don’t let your attachment to particular sentences or ideas prevent you from cutting them.

Just do it. Don’t convince yourself that an idea that it must remain in your draft at the expense of the quality of the work as a whole. However painful it may be, there will come a time when you have to sacrifice something for the good of the piece.

This fall, I wrote a piece for my journalism class, later published in the Daily Princetonian, about Princeton’s Career Services office. In the course of researching for the article, I interviewed more than a dozen students, alumni, and career service staff. Musicians and consultants, grad students and executives – everyone had their own story, their own advice to offer me and other students.

When I sat down to write the article, I wanted to include everyone’s story. I’d had many meaningful conversations, my interviewees were all interesting people (both in their careers and beyond), and I thought they all deserved to be heard. Never has the advice to “kill my children” felt more literal – every anecdote I cut from the article felt like a knife to the heart of one of the people I’d met through the piece.

Worse than removing people from the article entirely, though, was when I had to use only a small part of their story. How can I claim to be writing about someone when I have to compress an hour-long conversation into a mere couple of lines, or even a single sentence? Oftentimes the most interesting parts of people’s stories would be lost, their lives reduced to simplistic examples to prove their points.

But cut I did. The most interesting parts of people’s lives are not the part of their stories which made the best contribution to my piece. When you include evidence, an idea, or a story in your writing, you should ask yourself “what does this show the reader?” If the answer is “nothing” or even “nothing relevant to my argument,” even the most interesting anecdote is suspect. If cutting a particular part of your piece is painful, you should ask why you want to keep it – maybe it shows where the focus of the piece should be, or maybe it points towards a topic for future research.

Emma wrote last week about a new approach to writing, in which the author explores the full scope of an idea from several perspectives instead of focusing too much on a single narrative or argument. This is almost certainly the approach you will take to your thesis, and to other large projects — and in these situations, the need to cull is certainly far less. But even then, your reader will be best served with a series of clear, albeit interlocking and nuanced, narratives. If you find yourself going on a tangent, remember the violent editor’s advice.

So all this research that you did – all the stories you kill – are they lost? Was that research a waste of time? Absolutely not.

Research is about digging through a morass of information to find the threads that are interesting and novel. The fact that you’ve found so many ideas to potentially share in your writing means the ones that you do eventually set together are the highest-quality ideas, most worth writing about. And the rest of them? They’re rather like the people who didn’t make it into my article. They were engaging, they pointed you in interesting directions, they informed the ideas that you eventually used. And they’ll stay with you the rest of your life, informing future research projects, or, in my case, future career directions.

So maybe “kill your children” isn’t the best metaphor at all. Maybe the best way to think of it is the painful decision that every parent eventually has to make: sometimes, the ideas you love the most can’t be contained in the writing you’re doing at the time – so, if you truly love them, set them free.

— Bennett McIntosh, Natural Sciences Correspondent