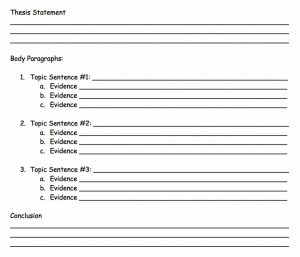

In middle school, I remember being told that the best way to write an essay is with an outline. We would receive five-paragraph-essay worksheets, complete with a thesis statement, sub-arguments, and important supporting information. It was direct, simple, and structured.

In this post, I hope to advocate for a different sort of writing. Outlines are certainly helpful organizational tools. But as I delve into my thesis, I find myself taking a more free-form approach. As I have previously written, I am writing on the legacy of pioneer Brazilian art therapist Nise da Silveira. Based on two months of ethnographic research, my thesis is about how da Silveira’s image is evoked and utilized by people who continue similar work. I have lots of interesting ideas, but no single, unifying argument. While writing an outline might be useful down the road, right now it would impose a limiting structure on my thought process.

Instead, I have decided to do what my friend Lily calls “Frankensteining.” To her, writing an essay is like creating Frankenstein’s monster: you have to find all the parts before you can sew them together and create a body. Lily explains:

“I think you need to Frankenstein when you’re developing any kind of complex argument because you can’t know what you’re going to say until you start figuring it out and seeing how different insights fit together. It’s writing as a nonlinear process — you don’t brainstorm and then write. They happen at the same time.”

In essence, “Frankensteining” frees the essay writing process from rigid structure. In practical terms, this means that although I have about fifteen pages of writing done, I have not yet written a coherent chapter. Instead, by pursuing a variety of ideas, I have arrived in unexpected places. Particularly, one section, about memorialization through funerals, would not have arisen so easily had I felt a need to fit it into an overarching argument. Though the distinct parts may feel somewhat disparate, I see how the more I write, the more I will find an organic through line.

A drawback is that I will almost inevitably overwrite, perhaps composing well over 100 pages of semi-related work. This is not necessarily a bad thing. When I have all the body parts, then I can make cuts and stitch them together. The artistry is in the rewriting.

To clarify, I am not arguing against outlines. I use them all the time! But as you approach a big research project, I urge you to hold off, at least at the beginning. For me, letting go of an immediate need for structure has granted me the freedom to explore new ideas. My thesis is an adventure that continually surprises me. And that makes it all the more valuable.

— Dylan Blau Edelstein, Humanities Correspondent