As I have written on this blog before, you unfortunately may not find all the material you need for a research project in Princeton’s own library system. Borrow Direct and Interlibrary Loan may help bring items from elsewhere to Princeton, but often with primary historical sources, you may find that you need to travel to an archive to view them. This is especially the case if the source you need is only available in its original form (and thus may be difficult for a peer institution to duplicate or send directly to Princeton), or if you are unsure of precisely what sources are available, and need to browse a collection in full.

I found myself in this position just a few weeks before fall break. As I explained here, I had just expanded my JP topic to consider a broad range of American antislavery responses to the Paris June Days rebellion of 1848. My adviser suggested I look through the manuscript collections of a number of prominent activists of the time. Many of them— such as Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, and Theodore Parker— worked out of Boston, and, as I discovered, a number of institutions there now hold their papers. I soon realized I would have to make a trip over fall break if I wanted to view all of these collections.

Train tickets were booked, housing arrangements were made, and off to Boston I went. It turned out to be a very fulfilling experience, but not without some bumps along the way. Here, I want to offer some advice based off of this experience for any other undergrad student planning to make a research trip.

Try to figure out far in advance if you need to travel. In my case, because of my topic switch, I did not realize I would have to travel until literally a few days before I left. This was pretty stressful to plan, especially considering I was in the throes of midterms at the time. The short timeline made every aspect of the trip more difficult, as I will further detail below. The lesson here is more about research considerations than anything else: it is good to cast a wide research net from the beginning of a project, so that you can find out early on if sources you need are far away. That way, if travel is not possible, you know to look elsewhere; or, if you know you can travel, you can begin planning accordingly. This leads me to my next few tips.

Explore a variety of funding sources early on. Though my adviser assured I would be fully reimbursed, and I indeed was, it was certainly not ideal (and not possible for everyone) that I had to pay out of pocket for every aspect of my trip at first. Though I was able to keep costs pretty low by finding last minute free housing with a recent alumnus I connected with online, I wish I had not been in a position where I had to desperately seek this arrangement on such short notice. Still, I will say, working through Princeton alumni networks on Facebook or Tigernet farther in advance would be a good way to secure cheaper housing for a trip.

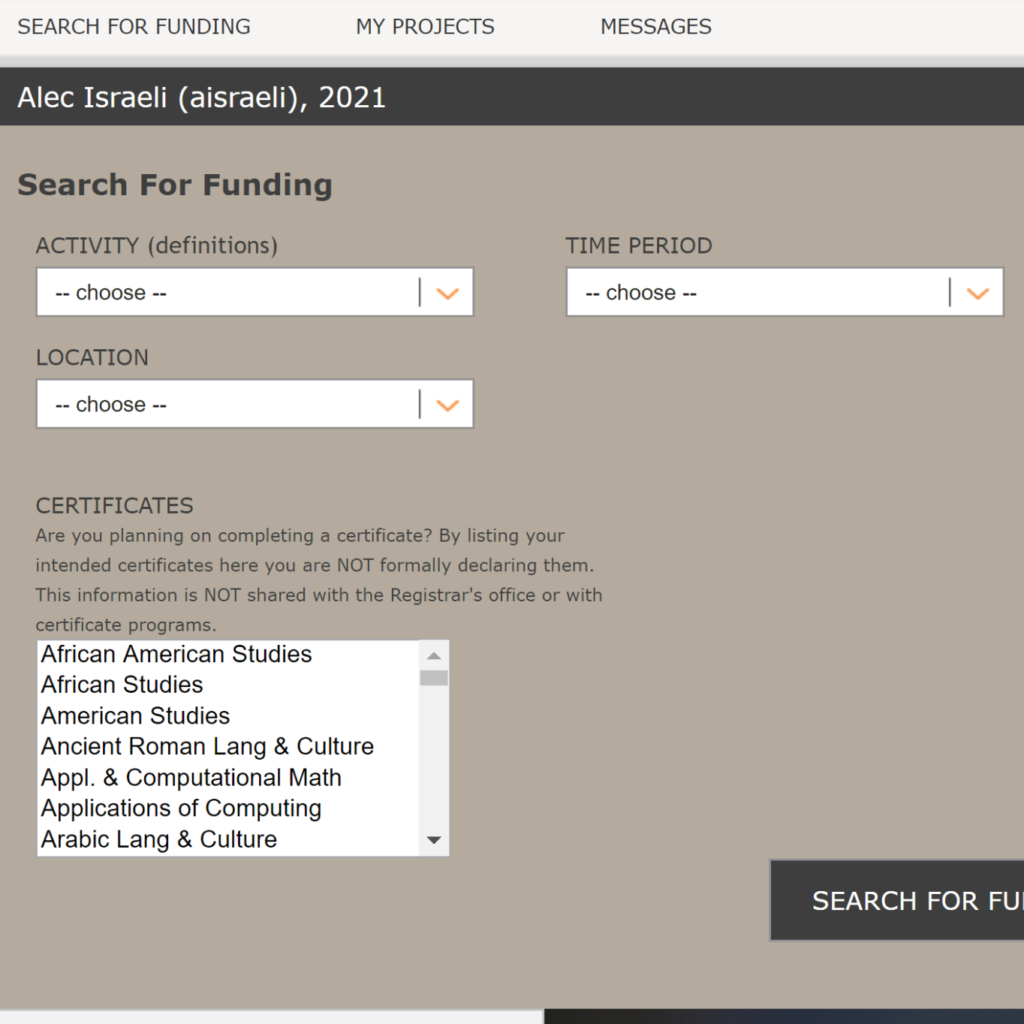

So, look for funding very early on, especially because some funding sources may take time to process applications. I would recommend browsing the Student Activities Funding Engine (SAFE), and playing with the filter settings based off of the nature of your research— you will see options to indicate trip location, duration, department affiliation, and other features. There are a wide variety of funding opportunities and programs that are often open for applications on a rolling basis. Many are topic-specific, so if your research fits a certain category, you could be a strong candidate for support.

Also, ask faculty and administrators in your home department and/or certificate programs if there is funding available for research trips. My own funding ended up coming from the history department. Begin with your adviser, your director of undergraduate studies, and your undergraduate program administrator. All three were a big help for me!

Plan your research trip day by day, and make sure your destinations are open! Now, the latter part of this advice may seem pretty obvious. But you cannot assume libraries or archives are open standard business hours (for example, the New-York Historical Society reading room is closed Sundays and Mondays, and is open from 10 am to 4:45 pm other days). So, check in advance. My mistake this fall break was pretty embarrassing: I had intended to visit the Boston Public Library, only to discover that their Rare Books and Manuscripts Department was closed for renovation until 2021! A simple google search in advance would have told me this.

This was a lucky mistake, though. With the time I did have, I was just barely able to complete my work at the other archives I visited at the Massachusetts Historical Society, Harvard’s Houghton Library, and Harvard Divinity School’s Andover-Harvard Theological Library. I realized I had been unrealistic with how much material I wanted to get through; had I gone to the public library too, it would have been unmanageable. So, if you are traveling for research, when planning your destinations day by day, always give yourself more time than you think you need. In addition to spending time in reading rooms, you will find yourself surprised at how much time everything else takes: traveling between sites, registering for access at each one, waiting for materials etc.

I hope that anyone looking to travel for research will find these suggestions helpful! I found my time in Boston to be a great hands-on learning experience, and I am looking forward to similar work when I begin thesis research this summer.

–Alec Israeli, Humanities Correspondent