“I can’t code,” I told my friends when I realized that I had to take a statistics course for my major that required coding. “I don’t understand it,” I told them. I had never coded before and the thought of creating algorithms on a computer sent shivers down my SPIA spine. I loved math in high school, and coding always seemed interesting to me, but rumors about Princeton math courses, as well as computer science courses, had me sprinting away from Fine Hall. But then, I realized I had to take a statistics course for SPIA. I had to face my fear of R, or the programming language that most SPIA statistics courses use for statistical computation. I didn’t think that I could do it, but I did. And, I ended up loving it. I faced my fears, learned how to code, and you can too.

I definitely recommend POL345: Introduction to Quantitative Social Science to any first time coders who are looking to apply code to a policy context. I chose to take this course not only because it counts as the SPIA statistics prerequisite, but also because I heard that it is a great way to learn how to code, and how to apply coding to things that I am interested in. COS126: Computer Science: An Interdisciplinary Approach is also an amazing introductory computer science class, which is taught in Java, but, for the purposes of this post, I will focus on the statistics route of coding. I had heard ghost stories about the SPIA statistics courses: “Coding for the first time is nearly impossible”, “you need to take a summer course before-hand”, “might as well change majors”. I can assure you that this gossip is not true. I entered the POL345 Zoom room and I had these hesitations in my head, but right away they were proven wrong by the excitement of Professor Ratkovic and the realization that this was the first time coding for many of my classmates too. We were in this together, and this is the mindset that you should take to your first coding-based class.

Based on my experiences coding for the first time in POL345, I have some advice that you may find helpful. In the course, we were assigned our first PSET two weeks in, and the content was surprisingly interesting and understandable. I used a combination of the precept assignments, my lecture notes, office hours, and the McGraw Center in order to succeed on the PSET. I also constantly exchanged ideas with my partner; typically, coding classes allow you to work with a partner, so it is important that you choose someone that you believe you work well with. I started the PSET early and I emailed my professor questions; don’t be afraid to reach out if you are confused, or even just to get to know your professor.

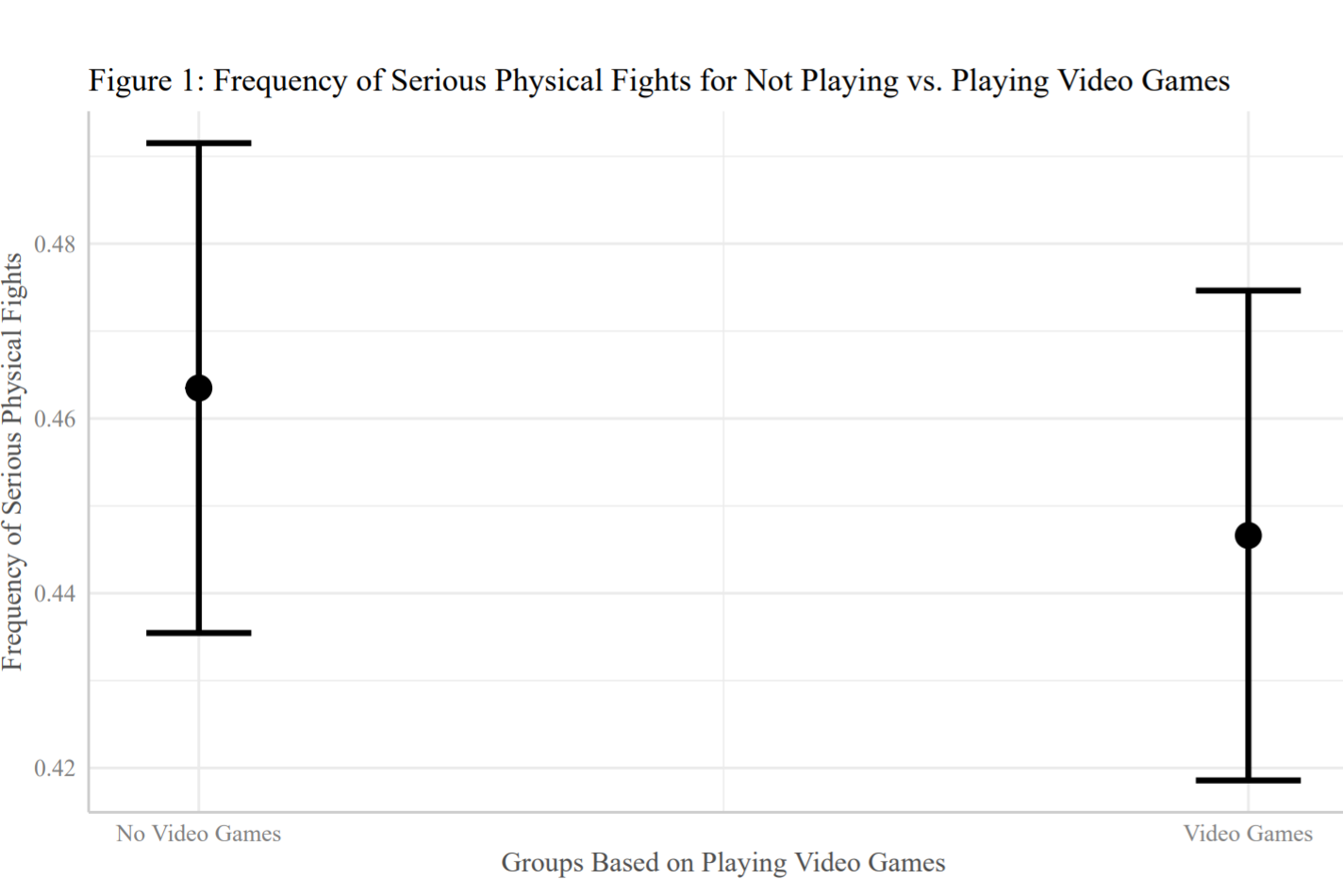

After the first few weeks, I no longer gasped in fear at the sight of the “Run” button. Actually, I started to love R. When my code ran, I couldn’t help but smile, and it amazed me how the problem sets had real world applications. For example, on one of our problem sets we used a bootstrapping technique to predict the winner of the 2020 presidential election using polling data from previous months (we predicted it correctly!). I was also able to explore exciting, less-academic topics in my next statistics courses, POL346: Applied Quantitative Analysis, such as video games. I investigated the classic belief that video games lead to violence and found that there is no association between playing video games and getting into physical fights for the sample of adolescents that I examined.

I zoomed into POL345 terrified of coding, and I walked out hoping to pursue a certificate in Statistics and Machine Learning. I took POL346 right after POL345 and was able to expand my coding skills and dive into R more deeply. Whether it is POL346, COS126, or SML201: Introduction to Data Science, each coding course will teach you something original and interesting. The point is that coding for the first time may be scary, but learning the skill and trying something new is worth it. If you put in the work and follow my advice, you will learn that coding and statistics can be impactful, and you will realize that you can do it too.

– Ryan Champeau, Social Sciences Correspondent