One of the major differences between the A.B. and B.S.E. courses of study at Princeton is that A.B. students are required to take (or test out of) at least four semesters of a language class. Studying a foreign language is, therefore, an essential part of studying the humanities at Princeton. There are many good reasons for studying a foreign language (besides simply needing to fulfill the language requirement)— perhaps you want to live or study in a different country, you might envision some professional advantages from knowing a foreign language, or you simply see studying languages as a new way to connect with others. Many Princeton alumni have successfully put their language skills to use in these sorts of pursuits. I’d like to offer another reason in addition to these: studying a foreign language at Princeton can prepare you to do exceptional research.

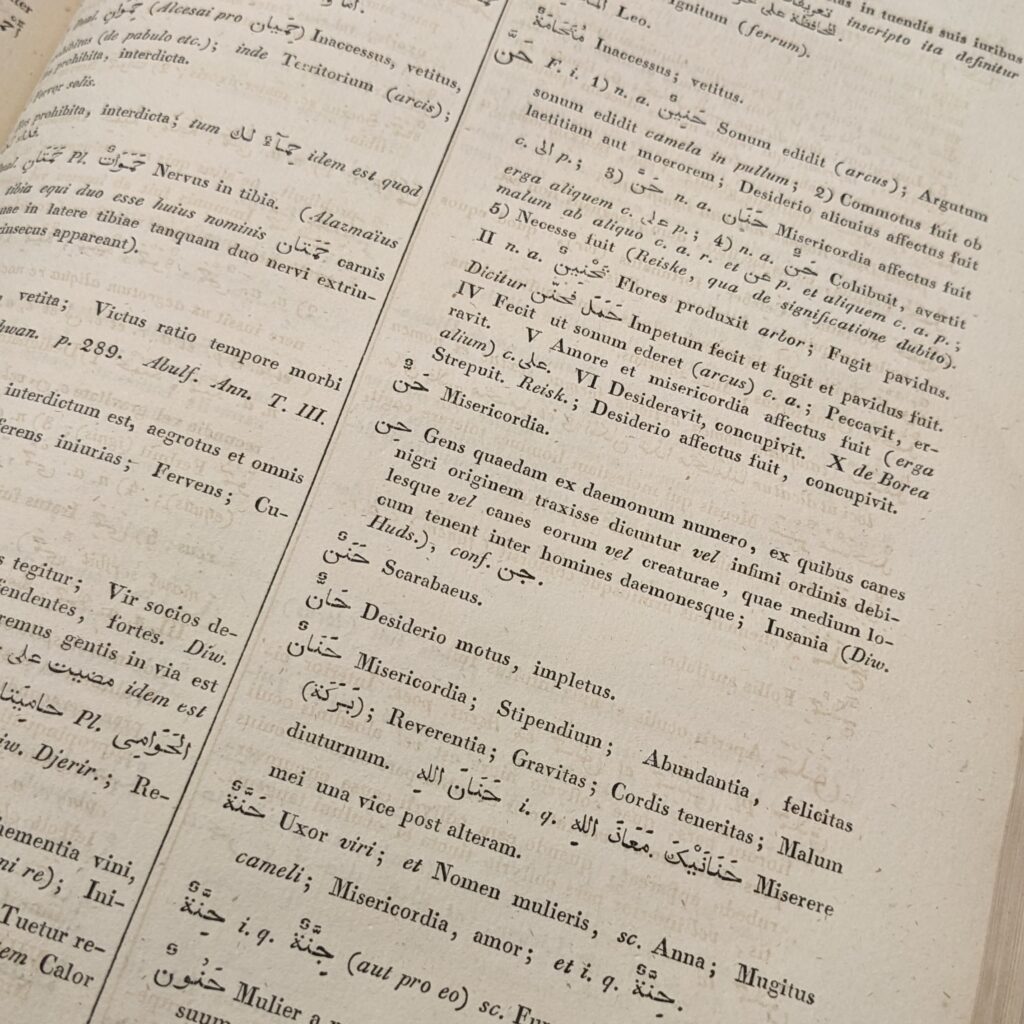

A page from an Arabic-Latin dictionary

It’s not a coincidence that Princeton both encourages undergraduates to pursue research, and that it requires many of them to study a foreign language. The ability to work in multiple languages is often essential for doing good research in the humanities. A big part of this is because of the emphasis on primary sources when doing humanities research. Unless your area of interest happens to speak only English— in the grand scheme of human history, this is exceedingly rare— you will need to know at least one foreign language in order to navigate primary sources within your field, and thus make strong claims. This is often very important when conducting research for your senior thesis or JP. You might want to work with unstudied or understudied sources, which are often not available in English and thus require the knowledge of a foreign language in order to be studied. Additionally, even with works that have been translated into English, knowledge of the original language is often necessary in order to grasp various nuances present in the work. In some departments— like German, or Comparative Literature, or my home department, Near Eastern Studies— the necessity of foreign language skills for research is clear. A scholar of, say, Slavic Languages and Literatures who did not know a Slavic language would probably have a hard time being taken seriously. But, even in departments without an explicit focus on languages, research which utilizes sources in a foreign language is always valued highly.

Languages can also help to guide you to a research topic. This was actually the case in my own experience. Having studied Greek, Latin, and Arabic, I wanted to find a point of contact between these three languages so that I could study a single topic using all three. I figured out, after talking with professors and other students, that the study of Christian-Muslim relations in the Middle Ages was the point of contact that I was looking for. I have greatly enjoyed studying and researching this topic, and I largely have language study to thank for this. Someone who knows, say, Japanese and Portuguese would be able to do amazing research on Portuguese Jesuits in Early Modern Japan or the history of the Portuguese Empire’s trading interests in East Asia. There are many other hypothetical examples I could give of how knowledge of different languages can set someone apart when studying a particular topic.

Research often is an opportunity for students to study a topic which they are uniquely positioned to study because of how it is connected to their different interests and skills. Language can help guide you to those intersections of interest. When thinking about research topics, or when studying a language here at Princeton, be sure to keep in mind the important relationship between language study and research. Such an approach will certainly benefit you over the course of your time as an undergraduate researcher at Princeton.

—Shane Patrick, Humanities Correspondent