Many Princeton students, when writing their senior theses, will be required to submit something resembling a “literature review,” where they give a broad summary of the extant literature on their respective senior thesis topics. Surveying the extant literature on a topic can help students to develop their own independent thoughts on the matter. For many students, the literature ends up being a very important part of the actual final text of the senior thesis.

After reaching this stage when researching my senior thesis topic, a relatively-unknown Arabic Christian legal text from 18th-century Lebanon called the Mukhtaṣar al-Sharīʿa of ʿAbdallāh Qarāʿalī, I realized that only a few paragraphs and couple footnotes had been written about the text in English. All told, the entire body of English-language academic work on the Mukhtaṣar totalled a mere two pages. This lack of a developed scholarly conversation about my topic came with its own challenges and opportunities. The relative obscurity of this topic was a large part of why I chose to write my thesis about it— I found it to be very intriguing and wished there was more written about it. In this post I intend to look back at my own experience writing a thesis on such a niche topic, and hope to offer some considerations on how such a project might be approached.

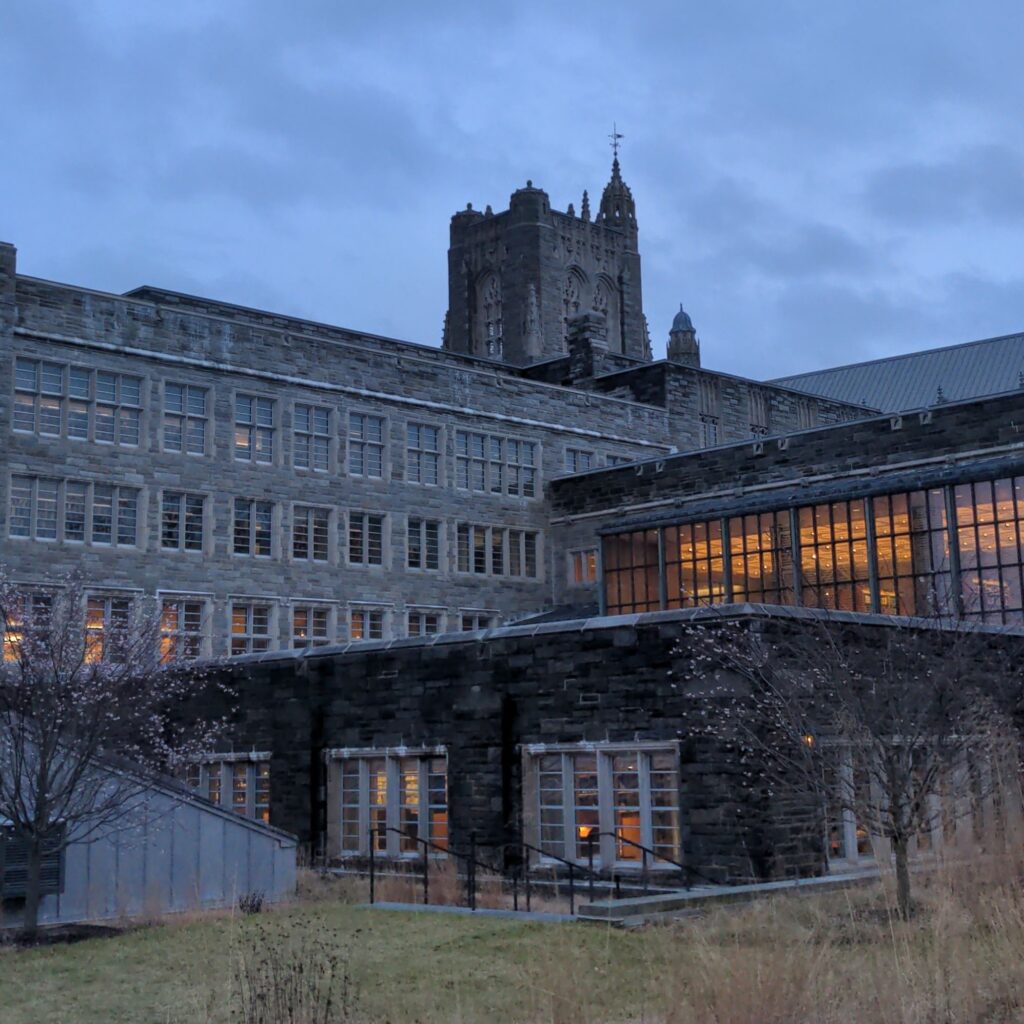

Firestone Library on a Spring Evening

My Experience

In my view, there were two main problems which stemmed from the lack of scholarship on my thesis topic and which I had to find a way around. First, if I didn’t understand something about the text, there was nothing which I could consult for a simple explanation. Second, I would have to work hard to find material to argue for or against. I approached these issues through two main avenues. First, I made use of scholarly writing which was not written in English. After doing a bit of digging, I uncovered a few sources written in German, French, and Arabic which discussed my topic. I used AI-based translation software to get a rough translation of the French and German works. While there are definitely pitfalls associated with such a move (these translators are sometimes inaccurate, although on the whole they do a good job of rendering long texts from European languages into English), it allowed me to access useful information much more easily, and I made sure to look closely at the original French and German for any quotations I leaned on in my thesis. I just had to work through the Arabic material on my own. To some extent, the lack of scholarly work on my topic had been an illusion— broadening my horizons to include non-English materials made my thesis much stronger. My other strategy was to look for more information about topics which had less-obvious connections to my text and look for parallels. Sometimes I would find these hidden in the footnotes of articles which discussed my topic, often they were recommended by a professor, and occasionally they were even readings I had done in previous Princeton coursework. For example, an article about a 13th-century Syriac Christian legal text from Iraq was very important to me because it showed me different ways to approach my own 18th-century Lebanese Christian legal text.

When I read through older scholarship about my thesis topic, I got the sense that little had been written about this text because scholars had treated it dismissively, either claiming that it was just like every other legal text of its time or instead emphasizing one highly unusual aspect of the text while ignoring the rest. After looking at the text very closely for a number of months, I didn’t agree with either of these arguments, and so I decided to write about the text’s approach to older legal texts. I really enjoyed this process, in large part because I didn’t have to worry about the possibility that someone had already made the exact same argument. Choosing such an under-the-radar topic gave me great liberty to argue along whatever lines I liked best and to chart my own path of thinking.

What You Could Do

One of the amazing things about pursuing research as an undergraduate at Princeton is that you have the freedom to study just about anything. You can tackle the biggest questions in a field, or you can look at something that nobody has researched in-depth before. Some advantages that I found while looking at a more obscure source was that I was able to look at it from a bigger angle (as opposed to looking at a very particular aspect of some more prominent topic) and ask bigger questions. Not having to wade through tomes of previous scholarship was both a blessing and a curse, but I really enjoyed researching in these uncharted waters. If this sounds appealing to you, here are a few things to consider.

Finding a very niche topic could be difficult. If you do end up studying something like this, you’ll probably come upon it by accident. It is hard to find “undiscussed” subjects through a standard library search precisely because they don’t show up in the sources where you would normally look. If you do end up finding a very under-the-radar topic which excites your interests, you might also have a bit of a harder time finding an adviser, since your proposed topic might not align perfectly with any single professor’s field of expertise. In my case, I stuck with my JP adviser because of how much I had benefited from his advising while writing my JP, and was confident that he could help me tackle this topic. Once this hurdle is past, your adviser will be your greatest ally. No matter how obscure your research interests are, your adviser will be able to connect it to better-known areas of study and to suggest helpful strategies for tackling such a singular topic. Princeton has many resources to support seniors writing their theses which you can absolutely take advantage of. No matter how mainstream your topic is or isn’t, the thesis process can be a very rewarding experience and there are many people at Princeton here to help you succeed.

Shane Patrick, Humanities Correspondent