It’s that time of year: freshmen get their first taste of research at Princeton through their third Writing Seminar assignment, quite unaffectionately known as D3. D3 defined my life in the last few months of 2014. My entire daily schedule was built around it. But at the end of the day, it was probably one of the most rewarding experiences in my life.

Through D3, I discovered a simple formula to find engaging research or project topics that would enhance my academic experience at Princeton. To this day, I still use that same formula, which I call the method of missing links, to stay engaged with my research.

Flashback to December of last year. I sat in my room utterly puzzled. I was supposed to write a paper that actively engaged with 10-12 scholarly sources in order to create an original argument. The last scholarly source I had read took me over five hours to fully understand. Now I was being asked to take 12 of these sources and use them in the framework of a larger self-created idea. And I wasn’t even given an end goal – I had no idea what I was supposed to prove.

I didn’t even have an idea of where to start. All I knew was that I had to write something about animal studies, the topic of my writing seminar. The lack of instruction wasn’t liberating. If anything, it was making me go crazy. What if the topic I chose had already been heavily documented? What if I couldn’t find a satisfactory thesis or motive? Worst of all, what if my topic just wasn’t interesting?

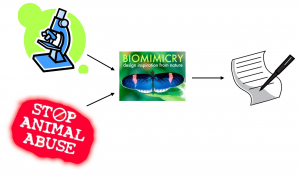

There were so many things that could go wrong, and I still hadn’t even found a topic. That’s when I thought, What would I do if I was writing about science? – where, for me, writing research papers was relatively straightforward. What interests me in science? I thought back to my high school science days, and the first thing that came to mind was an experiment I did using dye-sensitized solar cells. These solar cells mimicked the natural process of photosynthesis by replacing semiconductors with photosensitive dye from berries. This idea of miming nature to create innovations is known as biomimicry, and it was particularly interesting to me as a high school student. Although I had only learned about plant-related biomimicry, it wasn’t hard for me to discover that animal-related biomimicry was equally interesting. I had myself a general area of interest.

Before coming up with a thesis, I took my professor’s advice and fully researched biomimicry. As I read several books on biomimicry, I could only seem to find information about its environmental and scientific impacts. This frustrated me. I was supposed to write about animal studies and there was no apparent link between animal studies and biomimicry. For several days, I contemplated changing my area of research entirely until I thought to myself, “If the link is missing, why can I not create it?”

And right there, I had found my scholarly motive. The fact that I had literally started with nothing and just used my interests and thoughts to create an original idea was immensely self-satisfying. What I had originally perceived to be worrying freedom turned out to be the defining reason why my research was really important to me.

I had literally started with nothing and just used my interests and thoughts to create an original idea that was immensely self-satisfying.

What did I learn from this experience? Definitely a lot about animals and biomimicry, but also an important lesson for all you D3’ers: To find a satisfying research topic, you don’t have to overthink or agonize about finding a scholar-sanctioned direction. In research, there are an infinite number important missing links that have yet to be discovered. There are missing links between biology and chemistry, art and music, and even science and the humanities. Likewise, there are almost certainly missing links between your own interests and any given research topic. Finding one of these links automatically creates motive and opens up several different approaches to argue for the creation of that link. In finding a research topic, one doesn’t need to look too far to locate an argument. Look towards one’s own passions and the interdisciplinary links that are missing within those fields of interest.

– Kavi Jain, Engineering Correspondent