I’m reading The Lives of a Cell, by Lewis Thomas – a biologist who did his undergraduate degree at Princeton before becoming a renowned science writer and getting Lewis Thomas Labs named after him. It’s a beautifully philosophical piece of writing, as Thomas draws parallels between the miniscule cellular networks which give us life and the massive, invisible human networks which give that life meaning. But what jumped out at me wasn’t one of the many scientific tidbits with which Thomas peppers his writing, but a quote Thomas uses from an essay by physicist John Ziman: “A typical scientific paper has never pretended to be more than another little piece in a larger jigsaw—not significant in itself, but an element in a grander scheme. This technique, of soliciting many modest contributions to the store of human knowledge, has been the secret of Western science since the seventeenth century, for it achieves a corporate, collective power that is far greater than any one individual can exert.”

Thomas, ever the biologist, goes on to compare the collective effort of scientists to the collective effort of termites building a nest. And indeed, if you’re okay with being compared to translucent-brown grubby insects, that’s an apt comparison. For this is how the scientific enterprise moves forward: incrementally with millions and millions of individual papers (and now, in the age of big data, individual genetic sequences, chemical structures, geological maps, or other data points). But, especially early on in your research career, it’s important to remember that, however wonderful the collective efforts of termites are, research is much more than that.

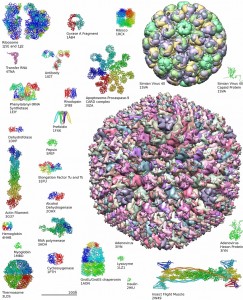

It can be a beautiful thing to hold a publication in your hand, or see the structure of a protein you discovered on the Protein Data Bank for all of science to benefit from. But sometimes that won’t happen. Sometimes, your thesis will sit in Mudd library for years after your graduation and be read by … nobody. Sometimes your experiments will fail and you will finish the project with nothing to show for it. In the course of my own thesis work over the last year, I have had to adjust my expectations, moving from asking “will this technique create a revolutionary, new type of molecule?” to “why didn’t this technique create a revolutionary, new type of molecule?”

How do we justify it when our contributions to human knowledge aren’t merely insignificant, but literally zero, especially when we’ve poured our heart and soul into our research? After such a project, you could think “If we were termites, I’d be the confused termite moving little specks of gravel around instead of building the nest.”

It’s a good thing we aren’t termites, then, isn’t it?

For one thing, individual humans can actually think forward to the long-term consequences of their research. And these consequences can be more specific than just imagining yourself throwing another bit of knowledge, like a mote of earth, onto the growing pillar of human understanding.

For example: A few months ago, eating brunch at 2D Co-op, I happened to be sitting next to a geosciences graduate student and an environmental engineer – both guests of the co-op and unacquainted with each other. The grad student was complaining that she believed her research – about how various micro-organisms process metals – was vaguely interesting but not immediately useful. That’s when the environmental engineer cut in. He explained that he had to think about how life deals with heavy metals in the soil every single day, and that every bit of knowledge added to the literature was invaluable in helping him and his team prevent and clean up after environmental disasters. Whatever field you work in, you can – and should – find projects that add knowledge to the world in a way that you find meaningful. This isn’t just for your own sake: it means your work adds more to human knowledge in general too, since you’ll feel committed to it and do better work.

You aren’t a termite, because you have individual goals and aspirations that matter just as much as the academic monolith you contribute to. That’s why they call us students and not drones.

But even thinking about how our research helps the world doesn’t provide the whole story. It’s important, too, to remember that you aren’t a termite because you have individual goals and aspirations that matter just as much as the academic monolith you contribute to. That’s why they call us students and not drones. The purpose of my life is not to build a nest.

So I hope that my research does something worthwhile for humanity – and indeed, understanding how proteins fold is an important goal. But in the course of my thesis work, I’ve also learned innumerable lab skills, proved to myself that I have the wherewithal to devote a year of my life to a project of this size (or at least will hopefully prove that when I turn in my thesis in two months), and gotten the chance to think scientifically and philosophically about the beginning of life on earth and the meaning of my life.

Take that, termites.

— Bennett McIntosh, Natural Sciences Correspondent