“Women aren’t meant for research. Get out of the research field while you still can.”

I heard those two sentences during the summer of my freshman year. I was at a summer research program, and the woman who told me this was the last person I would’ve have expected to discourage me from pursuing research. She was an associate professor from China working in the lab for a year and seemed very successful. But as it turned out, she had many buried regrets and concerns about her choice of profession and had come to question her own abilities as a woman researcher.

From the start, she was extremely nice—she even helped me buy groceries since I didn’t have a car. In return, I acted as her translator for difficult terminology (technical and otherwise), and helped to proofread her English emails. At the same time, this professor seemed constantly stressed, frustrated by her limited English skills, always worrying about taking care of her son while balancing research duties, and would sometimes lament about how quickly her hair was falling out.

One day, it seemed that her stress had reached its peak. She pulled me aside and gave me a warning: choose a profession that was ‘more suited’ to women. She felt that, no matter how hard we worked, women would always be unable to compete with men in research. “There are some things that men are just better at doing,” she said. “Don’t be like me. Get out while you can.”

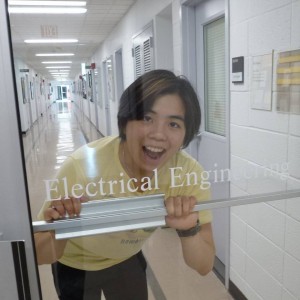

My elder colleague’s concerned words were like a douse of cold water. I felt terrible for her—I could tell how stressed she was getting. I don’t doubt she meant well in light of her own stress, but her words had me questioning my own path. Maybe I’d never be able to see things the way men did. Maybe Electrical Engineering was not a place for women. More than once, I asked myself a scary question: Should I get out before I ended up with the same regrets that she had?

More than once, I asked myself a scary question: Should I get out before I ended up with the same regrets that she had?

While I felt uncertain, I was also defiant. I worked as hard I could that summer—staying late nights and weekends, collecting data both with my colleagues and by myself to ensure that our sensor worked. All that effort paid off, and my successes in the lab convinced me to keep moving forward.

Thankfully, my subsequent experiences have been much more heartening. The following summer, I traveled to a research lab in Germany, where I met women who were more confident in their abilities. They were regularly consulted for troubleshooting, and they joked and played sports alongside the men. My superior was a brilliant woman who spearheaded multiple projects simultaneously in addition to leading a balanced family life. I was encouraged by them and the progress I made in my projects while I was there.

I also met great role models in the Princeton University Laser Sensing Lab, where I currently work. There were two female graduate students when I joined, and they were completely at ease within the ins and outs of research. One of them was even an active proponent of women pursuing science and engineering, and her desk was always littered with her nametags that read “Society of Women Engineers”. What was more, in the fall of my junior year, two additional graduate students joined our ranks, and they were both women. When I joined a new methane sensor project this past summer for my thesis and had the opportunity to work with one of the new graduate students, my adviser happily remarked that it was the first time he had a team full of women. I felt proud.

Other than my initial experience during my summer research program and the skepticism of some of my Taiwanese relatives, I’ve had the privilege of being surrounded by a supportive environment as I’ve pursued my path in Electrical Engineering, which was instrumental in helping me develop my confidence as a female engineer. Having positive role models can make all the difference, and I think one of the best things that we can do for the younger generation of aspiring women engineers is to increase the visibility of successful women in research.

Perhaps that is the greatest thing I learned from those two sentences in the summer of my freshman year—that it is important for women in research to lift each other up and show each other a path forward. I have little doubt that the associate professor I met would have had a different outlook on women in engineering, if she had recognized herself as a member of a supportive environment.

–Stacey Huang, Engineering Correspondent