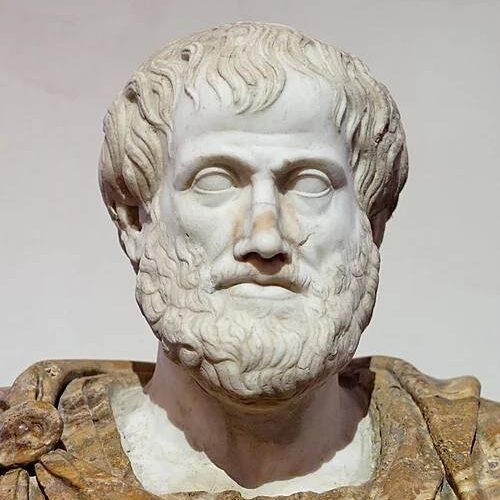

Aristotle’s Metaphysics begin with an oft-quoted adage: πάντες ἄνθρωποι τοῦ εἰδέναι ὀρέγονται φύσει (Aristotle, Metaphysics A.1 980a). “All humans, by their nature, strive to understand.”

With some spare time over fall break, I decided to brush up on my Greek philosophy. My upcoming junior independent work will focus on Lucretius’ philosophical poem De Rerum Natura, and he engages with so many ideas from ancient Greek thinkers – Epicurus, Democritus, Plato, and Aristotle, to name a few – I thought it prudent to be familiar with them. Given that the very purpose of their works is to explain their ideas, I didn’t expect to run into serious trouble as I began reading them. Instead, as I started making my way through Aristotle’s Metaphysics and Plato’s Timaeus, I found myself entangled with ideas of identity, causation, and substance. My overwhelming reaction was… “wait, what?”

I read and re-read the works, searched for commentaries and discussions online, and tried to make sense of how these ancient thinkers built their logic from specific principles and ideas, and how these ideas in turn influenced future ideas. Every time I thought I had a grasp on the content, another question would arise that I couldn’t explain. Understanding material leads to questions about what we don’t understand, and those lead to more nuanced and specific questions. That is the nature of a curious person, and anyone who gets involved with research will experience this confusion, whether that be in the library or the lab. For this reason, I love this Aristotle quote highlighted above. The word I translated above as “strive,” – ὀρέγονται, literally means “to reach out for,” or even “yearn for.” It takes a certain struggle to achieve enlightenment in any field. Wrestling through uncertainty, and working through question after question as they materialize, is part of the process of learning itself and should be recognized as such, not as a sign of failure.

While working through confusion is certainly valuable, we also need methods to understand our content. My solution has always been pedagogy. I spent the next hour pacing the yard, chucking a frisbee for my neighbor’s dog and trying to explain to him theories of matter, form, theology, identity, and will. Later, I repeated the exercise at the dinner table with my family, piecing together fragments of arguments and logic I hoped to develop in my research paper. Explaining concepts aloud and trying to explain them forced me to defend them coherently, and made evident any weak arguments or gaps in my understanding.

The traditional medical model for teaching doctors-in-training is “see one, do one, teach one.” The moment you try to teach something to someone else, you discover what you do or don’t understand. In this regard, teaching is part of the learning process itself. The act of articulation, whether it be fumbling through thoughts aloud, testing examples, or defending bad ones, clarifies understanding.

This process extends far beyond philosophy, where there’s never really a correct answer. I find myself regularly working through these feelings of uncertainty in my STEM classes and use similar processes to master them. I used to study in classrooms late at night, drawing out massive mechanisms or synthesis problems for myself on chalkboards, pretending to lecture to an empty room. Now, as I study the process of glycolysis and other metabolic pathways for biochemistry, I walk myself through the logic of each step from a chemical point of view. “What are the steps that have to occur in order for the cell to maximize the energy it can harvest from a molecule of glucose? Why? How does that happen?” I ask myself. “Given this problem, what is the logical next chemical step as a cell goes about this?” Speaking through these questions and trying to explain them to myself as if I were a new student helps me consolidate both my knowledge of the topic and the reasoning behind each step, ensuring deep and lasting understanding over rote memorization.

Research in any discipline demands that you clearly and effectively articulate a problem or idea that you approach, and make it communicable to a broader public. As such, I consider research as a three-part process: identifying a question, finding the answer to that question, and then presenting the answer to others. Working through confusion will make it possible to frame a meaningful question in the first place, and will give you ideas on how to go about answering that question. From there, teaching the material to yourself and others further hones your mastery, and prepares you well for step three. Learning and research are processes that take time, deliberation, and patience – keep these ideas in mind as you work on your research!

– Gabriel Ascoli, Humanities Correspondent