February 28. I’m sitting in the basement of Guyot Hall, grinding dried algae with a mortar and pestle.

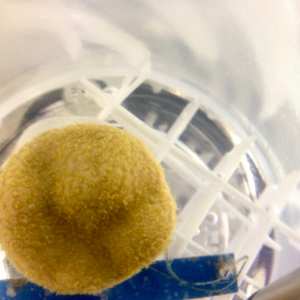

At this stage, Caulerpa racemosa, the Green Grape Alga, no longer looks its name. In its natural habitat, Caulerpa’s short stalks bob in the water like clumps of balloons. Its round “leaves” are clustered around the stalks just like green grapes, if grapes were the size of pinheads. But by now I’ve freeze-dried these samples so they are shriveled and stiff, and once I’m done grinding them, the plants are reduced to a uniformly fine olive-green powder.

This is what science looks like for me this winter. It’s not simmering test tubes or even statistics: just the incremental alchemy of water samples and crusty Caulerpa into numbers with the potential to tell a reef’s story.

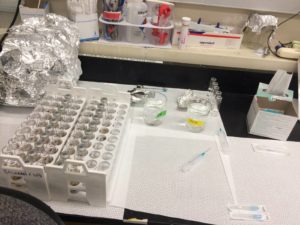

At a recent job interview, I was asked to talk about the lessons I’ve taken away from my research. One image that came to mind was that of my water samples: the hundred or so bottles that I filled in the ocean in Bermuda, carried back to Princeton in a cumbersome cooler, and spent much of this winter analyzing in the lab. Lined up in the freezer, the bottles are identical but for their labels. These bottles contain the most important data I have – and, for months, they’ve looked exactly like identical bottles of water.

But identical they are not. After many a long lab day, I have numbers to crunch – each bottle associated with nutrient concentrations and nitrogen isotope data that begin to tell the reef’s secrets. These nutrient data represent the raw materials available to plants and animals on the reef. The isotope data help determine where those raw materials have come from, and what organisms are using them. In my thesis, I am studying how nutrient pollution coming from human sewage changes the geochemistry of Bermuda’s reefs, affecting reef organisms, like Caulerpa, that use those nutrients. This has the potential to shift the ecosystem’s balance: nutrient enrichment puts reef-building corals at a disadvantage, threatening the intricate, biodiverse communities – of anemones and angelfish and everything in between – that corals support.

Continue reading Water Whispering: Memoir of a Winter in the Lab