I love my spring JP adviser. For one, he knows the biggest challenge of independent work is avoiding procrastination. As such, he’s preemptively strict with me on deadlines—pushing me to work on my JP for twenty minutes every day, and to meet with him at least twice a month to report on my progress. When we meet, he asks difficult questions, and provides incisive feedback.

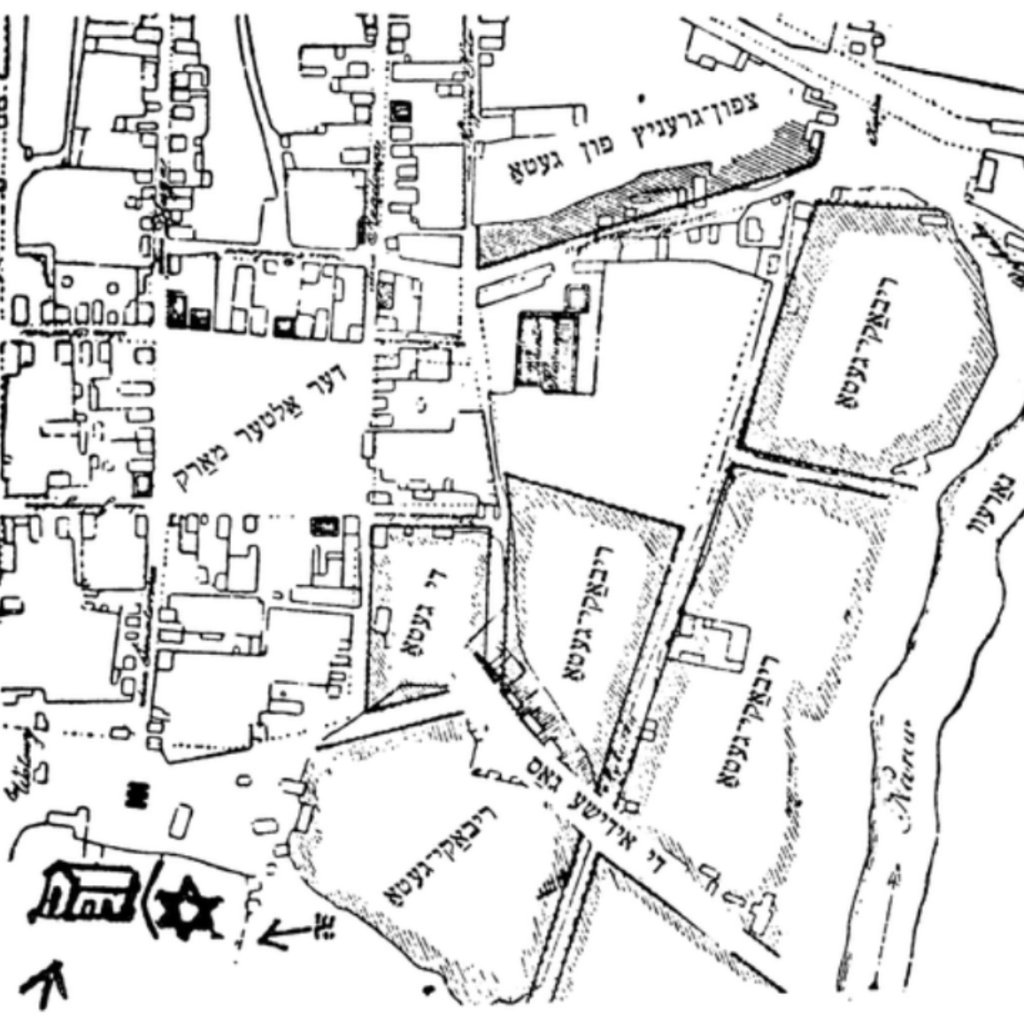

However, like any adviser, there is a limit to what he can provide. My JP project—which focuses on a series of maps produced in twentieth-century Yiddish memorial books— is actually quite distant from his area of expertise. He researches early modern Europe, a period nearly five hundred years before my topic’s. Additionally, I want my JP to engage with scholarship outside of the conventional boundaries of my discipline—particularly memory studies and theories of urbanism.

But at a university like Princeton, a mismatch between your independent research and your adviser’s area of expertise is by no means a dead end. Because of the diversity of Princeton’s academic program, there are almost definitely people on campus—whether graduate students or faculty—who can supplement your adviser’s mentorship.

In my case, I was looking for scholarship about mapmaking and its relationship to memory. I remembered a friend of mine had told me about a class on mapping she took last semester. I sent an email to the professor and a few days later, we met in his office to discuss my project. He provided me with a list of reading recommendations, highlighting the works most relevant to my research and attaching PDFs of the harder-to-find articles. He also encouraged me to look into “cognitive mapping”—a scholarly approach emphasizing the more personal, subjective elements of cartography. After only a few minutes meeting with him, I had a new treasure trove of readings and ideas at my literal fingertips.

To be sure, independent work will always be…well, independent. By definition, independent work requires us to develop expertise in a topic on our own, including locating and synthesizing sources for ourselves. But that doesn’t mean you can’t ask for help. Oftentimes, seeking advice from researchers in the field can lead you to works and concepts you may never have found on your own—or even known to look for. At the very least, speaking with researchers can be a major shortcut, connecting you with material it may have taken you hours to find on your own.

To find researchers in your field, ask your adviser if they know of other professors on campus with similar interests. Contact your professors from previous semesters, or ask your friends if they know anyone on campus who studies your topic. If you’re looking for guidance in a field outside your department, read through the faculty and graduate student bios on department websites, or contact the department representative and ask if they know anyone who might be able to help you. You can also find professors through Course Offerings—introducing yourself via email even if you don’t end up taking their class.

It can be intimidating to reach out to people you don’t know, but in my experience, professors and graduate students are thrilled to support students researching in their fields. Seeking guidance beyond your official adviser can not only save you time, but also add unexpected dimensions to your work—especially for a longer form paper like a JP or a thesis.

–Rafi Lehmann, Social Sciences Correspondent