Writing the literature review section for a scientific research article can be a daunting task. This blog post is a summary of what I have personally found to best help when writing about scientific research. I hope some of these tips can help make the process an easier and more fulfilling experience!

1. Create an outline for your paper

When I was learning how to write a research paper, I was taught that they must be written in the order of Introduction -> Literature Review -> Methodology -> Results -> Discussion -> Conclusion -> References. There exist many papers that stray from this arrangement, but no matter what style you choose, it should flow smoothly and tell a story. I like to think of my literature review as a means to situate my specific findings in the broader context of my research area.

2. Have a running vocabulary list at hand

Two years ago, when I venture into the unfamiliar field of fluid mechanics, I came across several unfamiliar terms like “von Karman vortex street”. I kept a pad of paper at my desk and would write these words down. Then as I read the papers, I would take note of how different researchers explain the ideas differently. This would help me form my own understanding of the terms which turned out to be incredibly helpful when trying to define it myself when writing my literature review.

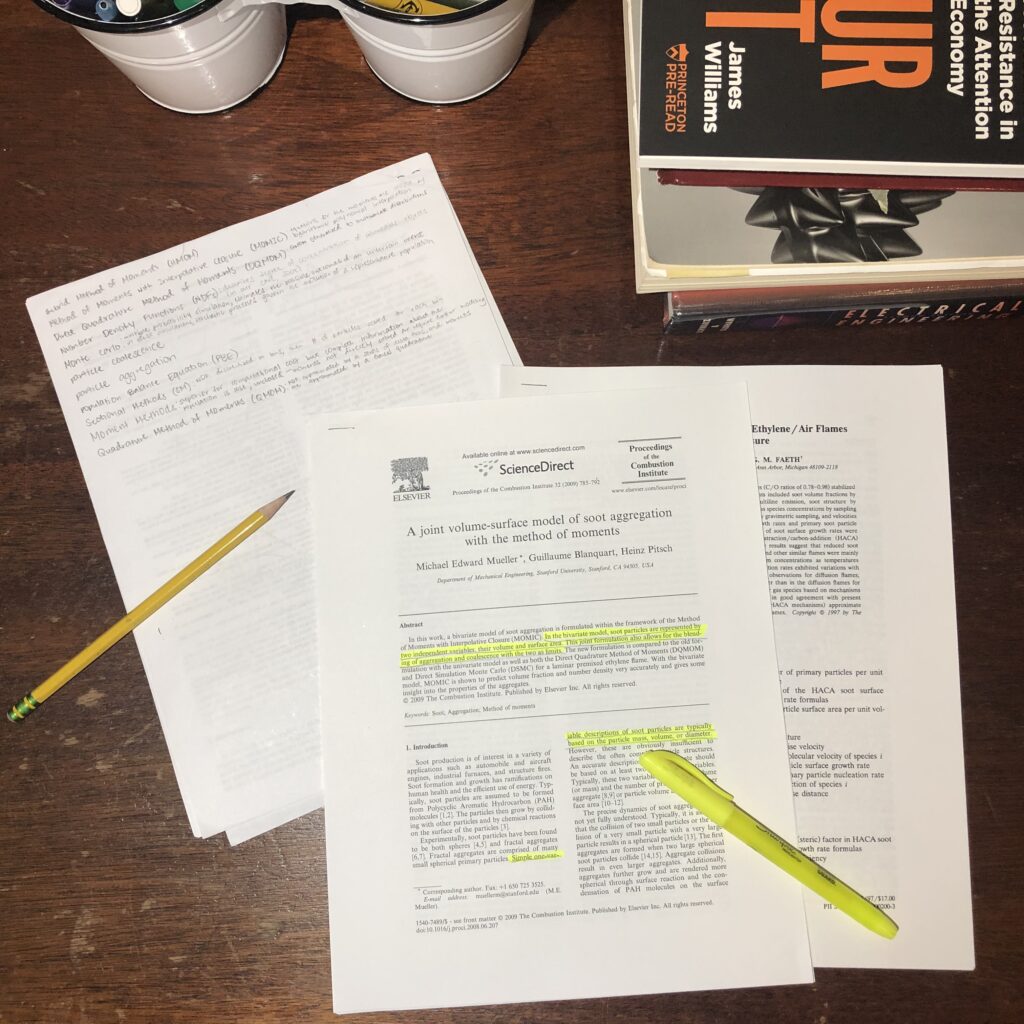

3. Highlight and annotate the papers you are reading

There is a lot to process when reading research articles, so to maximize your learnings, try to be an active reader! Highlight and take notes while you read. This was even studied by Blanchard and Mikkelson to improve performance outcomes in retaining what you are studying! This journals your thought process and can be useful when explaining the topics yourself as you write your literature review.

4. Summarize your notes/annotations in a master list

Especially if you are reading many papers, have a document or spreadsheet where you summarize the important parts. I also include my annotations and personal notes. That way, if I am writing my paper later and want to reference something but don’t remember where I read it, I have my master list to direct me back to the resource.

5. Have a separate document recording the important results and conclusions from each resource you used

Summarizing just the results across papers gives you a better idea of how the body of knowledge in your field has developed recently. You can also use this when writing your Results and Discussion section when comparing your own results to other research. I do this by “filtering” my summary and notes from the previous step to only include the results of the research. I focus on general trends observed, parameters and other independent variables, and arbitrarily chosen constants in research experiments.

6. Browse through the book or paper’s references/bibliography, other writings by the author/s, and other publications from the lab.

Whenever I read a good research paper, I look through the references to see the research that they cite often or seems relevant to my work, and I look up the author/s of the research and their lab to see other similar work they have done on the same topic. For example, in my current work in the Computational Turbulent Reacting Flow Laboratory (CTRFL), I have been reading papers by my adviser and from his advisers and colleagues when he was in graduate school. Also, don’t be afraid to ask for more papers, books, or other resources that your adviser can recommend!

7. Use a bibliography tool like Zotero

Preparing citations and bibliographies by hand can be a tedious and error-prone process. Using a tool speeds up the process of writing your bibliographies exponentially. However, do double check the auto-generated citations and bibliography to make sure that they are all correct. Here is a PCUR post that guides you through using automated bibliographies!

8. Let other people read your literature review!

Try to get someone in your lab who is not writing the paper with you to read the literature review and give feedback. They will likely be the best at spotting any major technical errors and will also have the best advice on how to write a paper in your field. Also try to get someone in your broader field but not working in the same specific research area to read it. (Try a classmate from the same major!)

Finally, please take all these tips with a grain of salt. What works for me may not work for everybody. Do try out different techniques to find what works best for you and makes you the best researcher you can be!

— Agnes Robang, Engineering Correspondent