I remember it like it was just yesterday. The steps to the scientific method: Question. Research. Hypothesis. Experiment. Analysis. Conclusion. I can actually still hear the monotonous voices of my classmates reciting the six steps to the content of the middle school science fair judges.

For our middle school science fair, I had created a web-based calculator that could output the carbon footprint of an individual based on a variety of overlooked environmental factors like food consumption and public transportation usage. Having worked on the project for several months, I was quite content when I walked into our gym and stood proudly next to my display board. Moments later the first judge approached my table. Without even introducing himself, he glanced at my board and asked me, Where’s your hypothesis? Given the fact that my project involved creating a new tool rather than exploring a scientific cause-effect relationship, I told him that I didn’t think a hypothesis would make sense for my project. To my dismay, he told me that a lack of hypothesis was a clear violation of the scientific method, and consequently my project would not be considered.

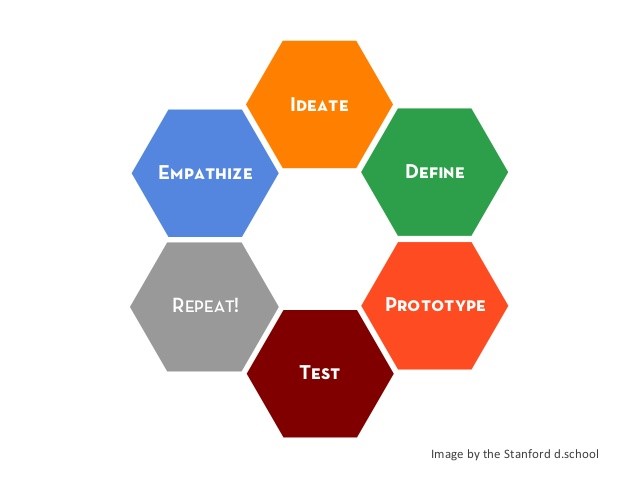

This was quite disheartening to me, especially because I was a sixth grader taking on my very first attempt at scientific research. But at the same time, I was confident that the scientific method wasn’t this unadaptable set of principles that all of scientific research aligned to. A few years later, my suspicions were justified when my dad recommended I read a book called Design Thinking by Peter Rowe. While the novel pertains primarily to building design, the ideas presented in the book are very applicable in the field of engineering research, where researchers don’t necessarily have hypotheses but rather have envisioned final products. Formally, design thinking is a 5-7 step process:

- Empathize – observing the world, understanding the need for research in one’s field

- Define – defining one particular way in which people’s lives could be improved by research

- Ideate – relentless brainstorming of ideas without judgment or overanalysis

- Prototype – sketching, modeling, and outlining the implementation of potential solutions

- Choose – choosing the solutions that provide the highest level of impact without jeopardizing feasibility

- Implement – creating reality out of an idea

- Learn – reflecting on the results and rethinking the process for endless improvement

But more generally, advocates of design thinking call it a “method of creative action”. In design thinking, researchers are not concerned about solving a particular problem, but are looking more broadly at a general solution. In fact, design thinkers don’t even necessarily identify a problem or question (as outlined in the scientific method); they are more concerned about reaching a particular goal that improves society.

This view of research is particularly insightful especially in disciplines beyond the scientific realm. One aspect that particularly appeals to me is the relative importance placed on the solution’s impact. In design thinking, researchers empathize. They understand at a personal level the limitations of current solutions. And once they implement their solutions, they learn from the results and dive right back into the entire process. Societal impact is their overall goal – an idea that carries over into humanities and social science research.

The most important aspect, in my opinion, is the freedom of design thinking. In design thinking, the ‘brainstorming’ process and the solution are given the most attention. Design thinkers are primarily concerned with the overall effectiveness of potential solutions, worrying about the individual details afterwards. This inherently promotes a creative and entrepreneurial research process. Combined with the methodology and analysis components of the scientific method, the principles of design thinking help research ideas blossom into realities. In a sense, design thinking repackages the scientific method to create a general research process in non-scientific fields. Artists, fashion designers, and novelists all use design thinking when creating their products.

So while I certainly didn’t impress the judges that day at the science fair, I did learn something far more resourceful than a display board could teach. In order to complete a satisfying research project, one doesn’t need to rigorously follow a well-outlined protocol. Often, all one needs is the drive to design creative and impactful solutions.

— Kavi Jain, Engineering Correspondent