At least once a week, without fail, I will stop in the middle of the p-set I am working on, or the paper I am writing, and think “what is the point of this?” Sure, the pursuit of knowledge may be a reward unto itself, but I don’t want my academic goals to be purely selfish–I want my course work at Princeton to benefit others. To this end, I have sought engaging research-based courses that can have a positive impact on people’s lives. These classes combine my academic interests with my desire for meaning, and provide a concrete ‘point’ to my course work.

Sure, the pursuit of knowledge may be a reward unto itself, but I don’t want my academic goals to be purely selfish–I want my course work at Princeton to benefit others.

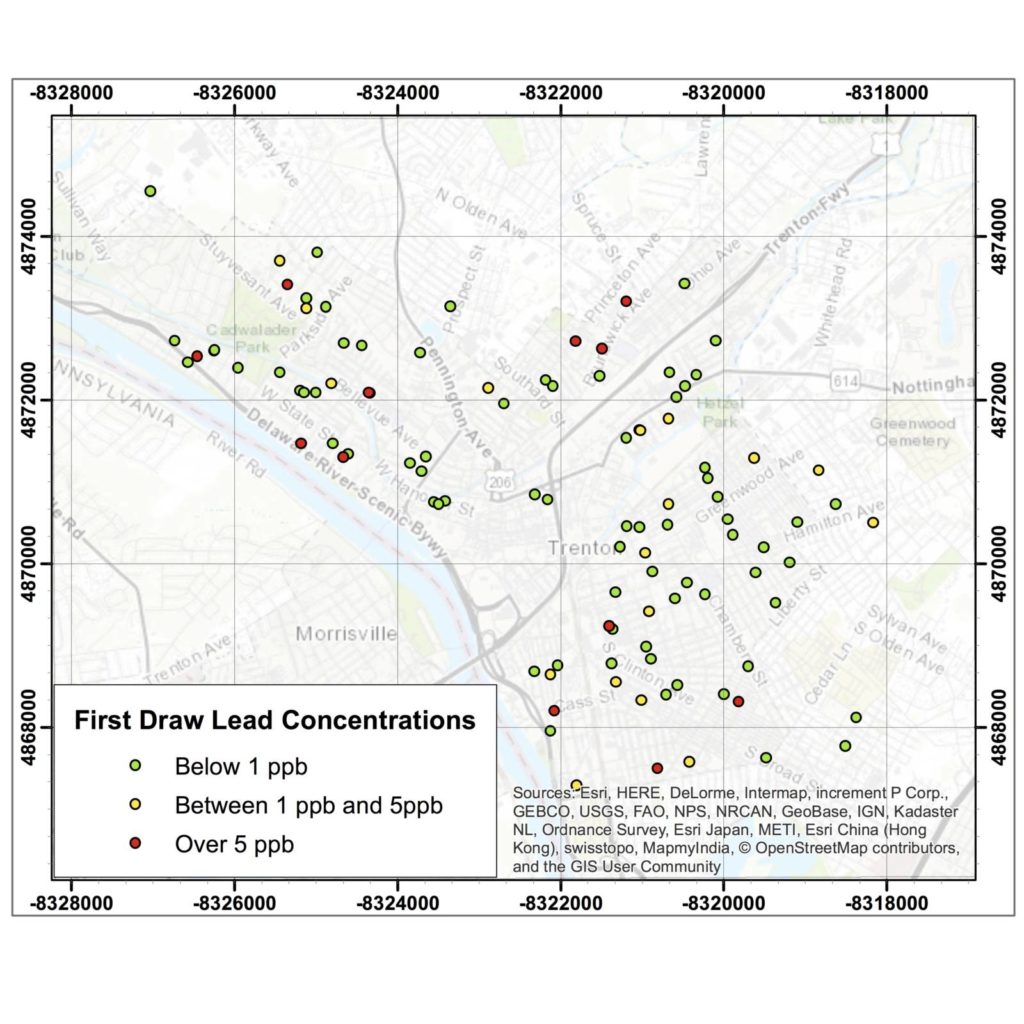

Last Spring, I participated in GEO 360, Geochemistry of the Human Environment, a course focused on providing chemical analyses of tap-water, paint, and soil for low-income residents of Trenton, NJ. Only 11 miles south of our orange-bubble along the towpath, Trenton is one of the poorest cities in the state and has a serious and systemic lead problem. Lead exposure is caused by the deterioration of lead paint into dust and the leaching of lead from pipes into drinking water. While lead paint was banned in 1978 and installation of lead piping was discontinued in the mid 1980’s, lead is still ubiquitous in Trenton where 90% of homes and buildings were constructed prior to 1978. As homes in the city age, the lead within them becomes mobilized and hazardous, and residents often do not have the financial means to keep their homes safe.

Our class worked alongside Isles, a non-profit Trenton organization that has tested over 2,000 homes for lead and provided remediation work–all free of charge–over the past three decades. We assisted Isles with field work by collecting samples, and measuring paint and soil lead in urban residences. We then analyzed hundreds of tap-water samples, measuring elemental concentrations with a mass spectrometer and conducting multivariate analyses to quantify the correlations between metals within samples. Our work helped Isles identify at-risk homes in order to provide them with lead paint remediation and/or water filters.

This combination of research and service provided an engaging and meaningful opportunity to assist the local community through my academics. Not once in that class did I question the ‘point’ of the course work; I could clearly see the problems we were combating–dilapidated houses, chipping paint, dangerous water lead concentrations–and I could see the solutions our work helped to provide.

I will continue seeking research courses that positively impact our community, and if you are struggling to find meaning in your academics, I urge you to do the same. While these types of courses have been few and far between in the past, the University is actively working to expand such offerings. If you are looking to merge your academics with service this Spring, take a look at the list of service-based courses offered through the Community-Based Learning Initiative. The numerous opportunities offered through the Pace Center are another great place to find ways to engage with the local community! From teaching dance to Trenton elementary school students once a week, to developing and delivering semester-long courses at NJ State prisons, there are many wide-ranging options available to apply your academic pursuits to helping others, no matter what you are studying.

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent