This semester, I’m taking REL 357/HIS 310: Religion in Colonial America and the New Nation with Professor Seth Perry. Even though we’re only in the fourth week of the semester, we’ve been thinking about the final project for the class already, since it consists of independent research on a primary source from Firestone Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections Division, pertaining to the history of American religion. In this post, I’ll be sharing some of my reflections thus far on this project, which I hope will be of use to anyone engaging in primary source research—especially those feeling overwhelmed by the sheer volume of materials available to work with!

My particular project has pretty wide parameters: basically, anything from the continent of North America pertaining to religion is fair game. On the one hand, this is quite liberating–I am free to follow my interests wherever they might lie. On the other, however, it is also easy to feel swamped by the thousands of objects in the library catalog that could fit the bill for this assignment.

With these thoughts in my head, I began to think about what I might want to research and write about. Thankfully, however, I wasn’t going at it all alone. Early on in the course, our class visited Rare Books on the C floor of Firestone and met with several of the librarians in that department. These people know quite a lot about their books, as well as the historical contexts of the myriad objects in the collection. And, to boot, they’re incredibly warm and welcoming to those uninitiated in the esoteric arts of primary source research. For these reasons, our visit to the library was quite helpful. I learned some of the key things to look for when examining an old book and trying to discern aspects of its history, which include annotations, paper quality, inscriptions and dedications, and any materials that come along “with” the book, including dealers notes or auction slips. And, during our visit, I got to physically handle objects that were owned (and autographed!) by a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Since I’m not Nicholas Cage in National Treasure, I don’t get to do that very often—so it felt pretty cool.

Inspired by the John Witherspoon and Johnathan Edwards collections, in particular, I spent some time in the days following our library visit looking for books, Bibles, and sermons from around the time of the American Founding. But, I was finding it difficult to identify books that were sufficiently annotated to make a significant argument about their circulation or readership. If you’re in this situation, don’t be discouraged—the best advice I’ve heard is to simply call titles that sound promising to the rare books reading room until something well-annotated or intriguingly-dedicated comes up. You can also speak with a Rare Books librarian to help narrow your search. (See this post about subject-specific librarians for more information.)

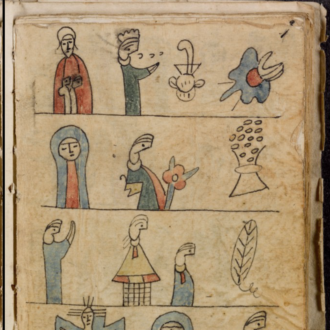

I, however, decided to take a different approach altogether. Reflecting on the wide scope of the project, and how materials related to Founding-era Protestantism account for only a small portion of what is available for research, I rethought my area of focus. On a whim, I scrolled through a list of some of Princeton’s Mesoamerican Collection holdings, and I was not disappointed. Within just a few minutes, I found this incredible artifact: a pictorial catechism, used by Spanish missionaries to attempt to convert the Otomi people of present-day central Mexico, dating to approximately 1800. Of course, this all happened in the midst of the brutal Spanish colonization of North America, so one must always keep in mind that such evangelism by Spaniards was not particularly welcome by the Otomi. However, I know that there is an important story to be told concerning the catechism’s troubling origins, as well as its implications for the study of religion in America. And I look forward to telling that story.

In archival research, as in other areas of life, sometimes you just know when a connection has been made, when you’ve found the right object or topic to investigate further. That was certainly the case for me when I came across the pictorial catechism. But there are many, many more intriguing objects in Rare Books, each with the potential to surprise the right researcher at the right time. (On this note, I heartily recommend checking out my fellow PCUR Rafi’s post on navigating the Rare Books collection.) Indeed, I would encourage any interested reader to tap into this incredible resource and to see for themselves what genuine historical treasures can be found only with only a few clicks!

–Shanon FitzGerald, Social Sciences Correspondent