As I have written for the PCUR blog before, choosing a topic for an open-ended research project can be challenging. Even once you have narrowed your search and settled on an idea you would like to pursue, you may find that other scholars have already written about it. There is indeed a finite number of possible research subjects (even if it seems, as I suggested in my earlier post, that there is infinite possibility), and as undergraduates many of us have yet to find our research niche. This by no means should discourage you! Just because there is existing literature does not disqualify you from making your own contribution. Of course, we are told this in our first-year writing seminars, where we discuss the different “scholarly moves” one can make (“piggybacking” on another scholar’s work, “picking a fight” with a scholar, and many others, as helpfully delineated in this paper).

In this post, however, I do not merely want to rehash what these “moves” are, but rather suggest how one goes about making any intervention, especially in determining what kind of intervention one wants to make. The following are some methods I have found useful in my research:

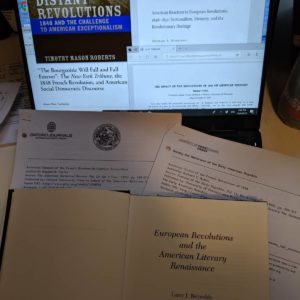

In your secondary readings, look out for gaps in the literature. That is, look for questions posed that remain unanswered, and for relevant questions you have that are not even posed; look for ideas or events which are mentioned but passed over with little exploration. For example, my current JP research focuses on American reactions to a French workers rebellion in June of 1848. While there is a substantial body of existing work on American reactions to the wider European revolutions that year (there were many), in the French case, I’ve noticed the scholarly focus has thus far seemed to remain on an earlier, different revolt that occurred there in February. American response to the June event— which was far more radical and violent— is comparably undiscussed. Here, I saw an opening for an in-depth contribution.

Another way to look for “gaps” is to identify the normative assumptions an author makes. Consider how the same topic can be addressed, but with these assumptions challenged. Are they outdated? Insensitive? Can you bring a new framework of thought to reinvigorate an old field? This brings me to my next tip:

Identify new strains of thought in your discipline, and bring them into your work. The main questions I want to answer in my current research involve antebellum American attitudes towards labor, democracy, and race. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of pages have been devoted to such concerns. However, I have found a lot of this writing is rather fenced in by the US border, not taking into account the international currents influencing American thought. For a number of years now there has been a sort of “transnational turn” in history research, which insists upon the interconnectivity of people, ideas, and events across the globe. Inspired by this, I want my project to help “de-Americanize” American history, and give new breath to old questions about American identity.

As you begin your primary source work, look for the strange, the wild, the uncertain, and the unaddressed in your materials, and you will be able to create your space within existing literature.

Look for the unfamiliar in primary sources. I make a similar suggestion in the post I mention above. While there I highlight the general richness of primary sources, here I mean to specifically point out their inherent versatility. Not to get too cheesy as a history major, but each source tells a story; indeed, each source tells multiple stories. If a source has already been used in previous work on a topic (which is very much the case for me, as I am using oft-referenced newspapers), there are still probably aspects of that source which have not been elaborated upon. Consider this piece of advice as a corollary to my first: gaps in literature often occur when certain sources have not been scrutinized as much as they could be. As you begin your primary source work, look for the strange, the wild, the uncertain, and the unaddressed in your materials, and you will be able to create your space within existing literature. This is how I came to my topic for my first JP, which studied the political thought of a mid-20th century South African Jewish journalist. As I initially read through his work, I kept thinking about how little airtime it received in South African Jewish historiography, despite how eccentric and odd it was. Such an inconsistency is what impelled me to eventually focus on this writing.

I want to close with a reassurance to my readers that we are not at all expected to make groundbreaking discoveries in our field with each paper we write, and nor are professional scholars. Rather, with my suggestions, I want to emphasize that the endeavor of research is incremental, collaborative, and cumulative. Without contributing to already existing topics of research, our respective disciplines would not progress as they have.

–Alec Israeli, Humanities Correspondent