Fall break – a time for rest and relaxation. While I certainly used the time to collect myself after the whirlwind of a more normal semester, I also had to make progress on my junior paper for the History department ahead of its first draft in November. Exploring a consumer’s perspective on post-war nylon riots (1945-46), I had toiled through various online newspaper archives to rack up an impressive number of sources; however, something was missing. I felt like I wasn’t going deep enough. I wanted to find someone’s thoughts on the riot outside of the newspaper databases I had used, which I knew would be a challenging (if not impossible) process that could only be achieved by looking at the archive.

An important tool in the historian’s kit is the archive, which is a trove of various historical documents, materials, and items that can transport you to another time. Given that the archive is a physical location, the pandemic had interrupted much of the on-the-ground work historians do in libraries across the country, much of which was overcome through technology. Thankfully, I was able to access wonderful archives in-person in my hometown of Pittsburgh, PA: the University of Pittsburgh Archives and Special Collections as well as the Senator John H. Heinz History Center Detre Library and Archives. Covering a vast array of local and regional history, I was set on taking advantage of these archives’ resources to further my research.

I wanted to use this space, then, to share a bit about (in-person) archival research and what I learned. Regardless of your academic studies or research, archives offer a window into the past that could helpfully contextualize your topic, explore an unknown tangent that can offer up a new perspective, or even just lose yourself in the archive looking at random things. In this article, I will specifically cover the process of identifying an archive and then finding items within that archive.

Wait, how do I know which archive to go to?

Well, I must counter: What are you researching? What is its geographic scope? Having a sense of your research’s geography is important; not only does it allow you to build a cohesive, impactful research question, but can help you identify archives that may be pertinent to your research. For example, I was certain I wanted to focus on the Pittsburgh region. It was only natural that I explored the two largest archives in the region, instead of putzing around elsewhere.

That being said, the geographic scope can only take you so far. As Alec pointed out in his wonderfully-written post, archives and library systems, while large, do not encompass everything under the sun. Inevitably, the resources you might need might be in completely different states or countries. Obviously, I would not recommend traveling to a random archive – it is important to do your research in advance. Speak with professors and researchers who are familiar with your topic, as they can give you insight on what archives might suit your interest. Check out a wealth of resources available to you as a Princeton student, such as WorldCat, ArchiveGrid, Archive Finder, or even the Library of Congress. Plugging in key terms from your research, Library of Congress subject headers, or the archive’s unique controlled vocabulary will point you in the direction of finding archives, collections, and materials that can further your research.

Once you find the right archive, you can plan a visit, request scans, or see if they have the material digitally available already.

Now I know where to go, but how do I find it?

Archives are big places with many materials. Items are not just put together randomly (usually), but organized into finding aids, put into collections, and stored in bankers’ boxes or other storage devices. Finding “it” is the hard part.

Thankfully, due to your use of WorldCat or other archive locators, you already located a collection that might be pertinent to your research. For instance, when I was looking for information on hosiery through ArchiveGrid, I found that the University of North Carolina had a collection for the National Association of Hosiery Manufacturers, something that I just recently requested to look at.

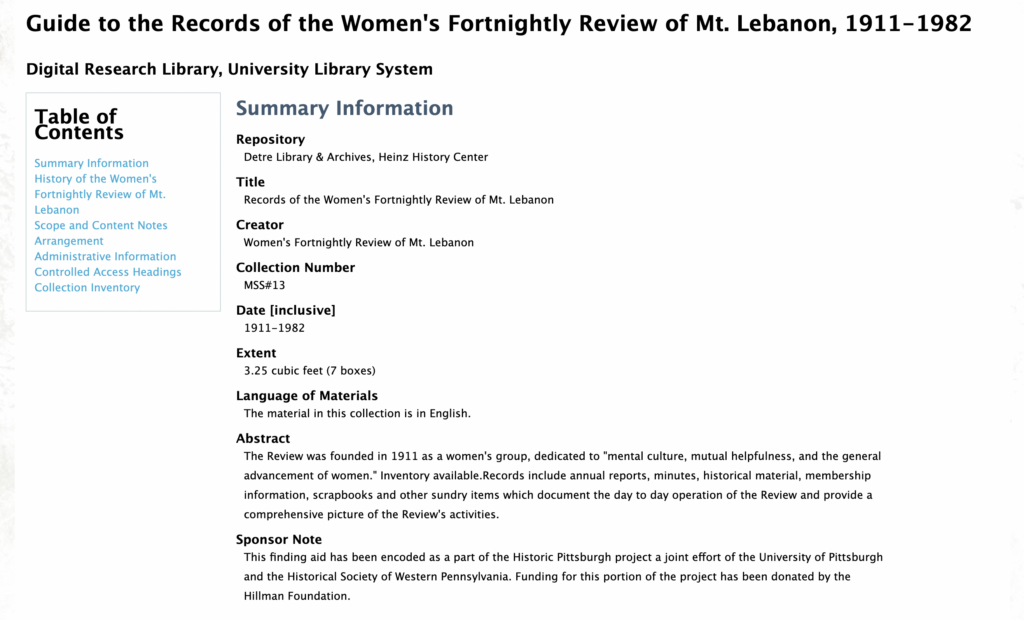

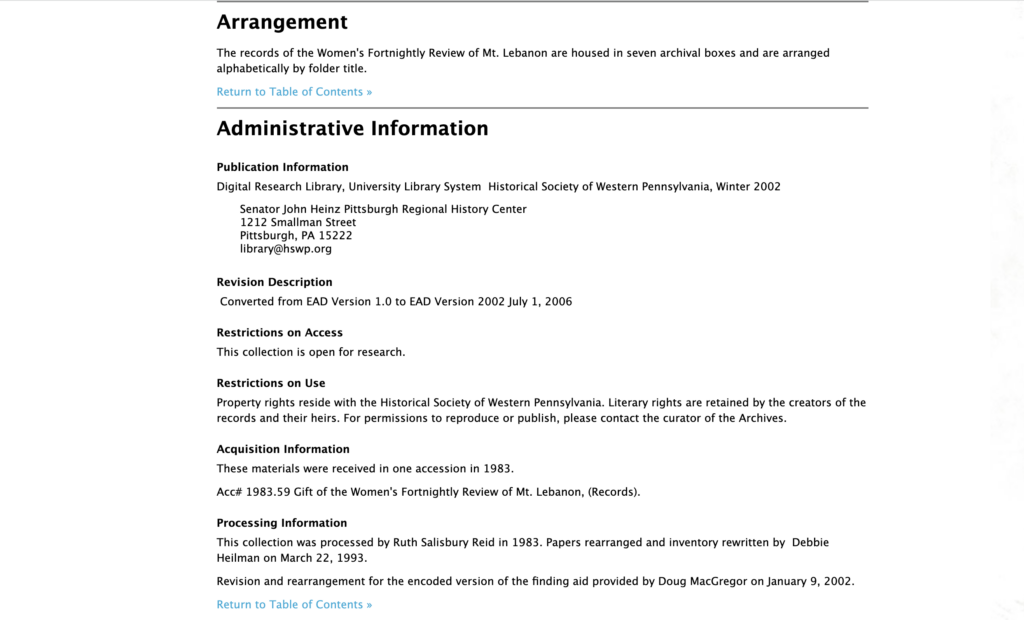

But what happens if you don’t know? This is where finding aids typically come in. Finding aids are tools that typically describe the basic metadata of the item in question. For instance, if we look at the finding aid for the Women’s Fortnightly Review of Mt. Lebanon from the Detre Library, we see we get a lot of information, such as the collection number, subject headers, a history of this specific collection, and the organization of the material. Archives organize their materials into a large array of finding aids, such as you see in the Detre Library. By making use of the controlled vocabulary, you can search through these finding aids to find ones that are relevant to your research. For instance, I focused on “Social – Women’s Clubs” (a Library of Congress term) to find the Women’s Fortnightly Review.

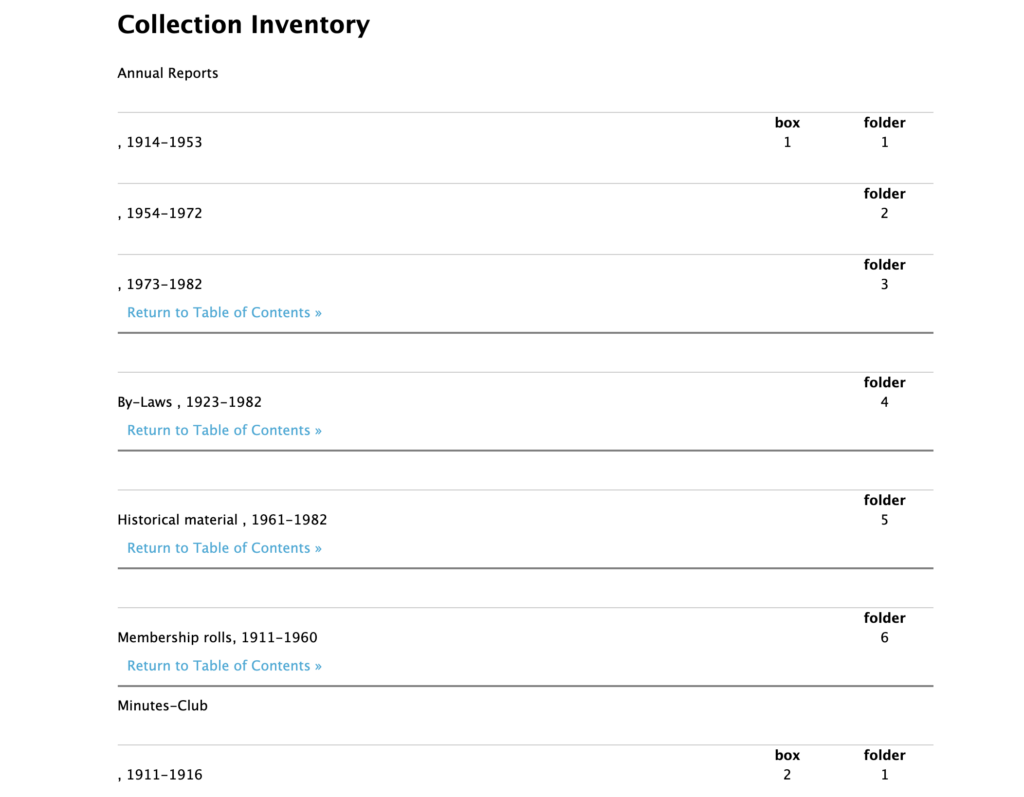

Once you find a finding aid that matches your interests, give it a read-through. You should pay specific attention to sections that describe the content and its organization. As you see with the Women’s Fortnightly Review, the section “Collection Inventory” breaks down what items can be found in what boxes and what folders. This information can then help you narrow down what to request and where to look.

If you have genuinely no clue on where to begin, consult one of the librarians at the archive. These wonderful people have a wealth of information about how the archive is organized and what materials could possibly be relevant to your work. It is also important to build a relationship with them as these will be the people who are scanning your work or fetching your items.

In the next article, I will share more about what you do in the archive – How do you behave at that moment? How do you take notes? What is good archive etiquette? These are questions that I had to grapple with as I dove into the archive for the first time without scaffolding, and I want to make sure that you land that dive perfectly.

– Austin Davis, Humanities Correspondent