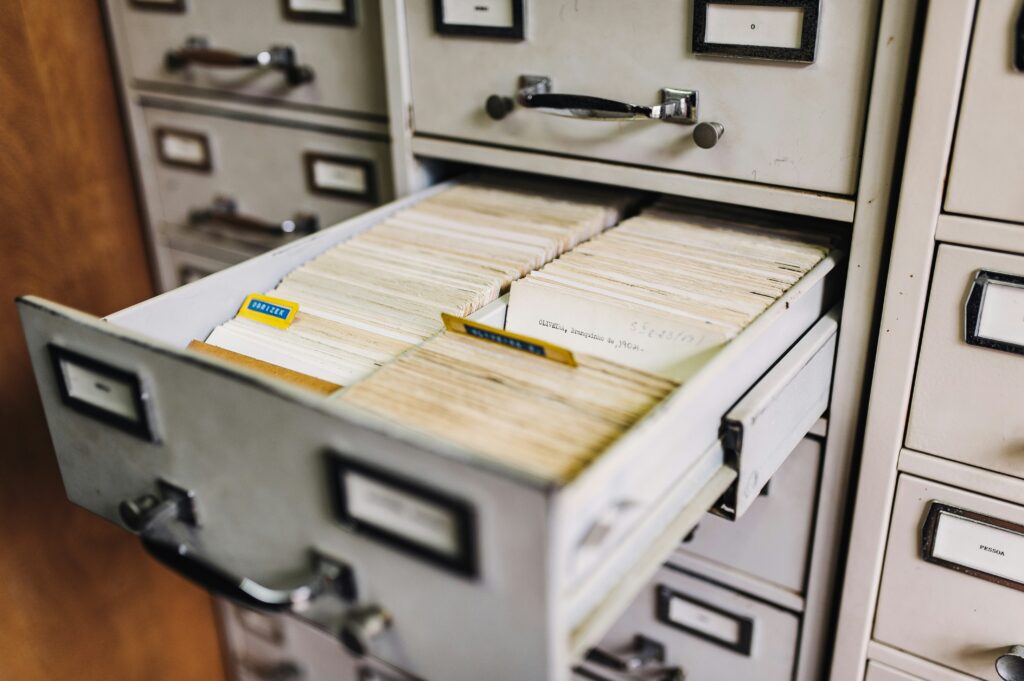

Many academic disciplines engage with visual art, whether from the standpoint of art history, material culture, or even paleography. The Princeton Index of Medieval Art is a unique database well-suited to the needs of researchers across various fields. Whether history, comparative literature, art, or classics, the index gathers a vast amount of information on Late Antique and Medieval Artworks, neatly sorted in an accessible way.

The Catalogue allows one to search by an array of categories (fifteen in all, excluding advanced search). Whether by region or motif, artist or patron, or language or script (for manuscripts), there is no shortage of ways to find what you are looking for.

Entries include several useful details, such as style, subject, and media (with links to further examples), as well as a description, dimensions, writings in which the artwork is cited, provenance, and current location.

For instance, perhaps you, like myself, are interested in heraldry and would like to know the significance and spread of the two-headed eagle as a heraldic symbol. Upon searching “Eagle, Two-Headed”, a vast array of iterations appears. Not only is it featured in the habitual Habsburg heraldry, but also in a Ge’ez manuscript, an Old French depiction of Julius Caesar’s accomplishments, and many other depictions of this symbol, which as it turns out, was by no means the exclusive domain of Holy Roman Emperors and Russian Tsars. Searching by subject allows one to compare different renditions of the same motif. A long list of options appears, from the generic to the very specific, historical and biblical figures, with detailed sub-variants (such as John the Baptist, Head on Charger) and a host of other examples.

Or perhaps you only wish to view items that are on campus for a chance to behold your subject of study in person. Fortunately, the Location list allows you to view the items held by the Princeton University Library. The dropdown menu “Associated Works of Art” reveals a long list of the Library’s collection, complete with descriptions of the motifs, place of origin, dates, etc. Another list details the holdings of the University Art Museum. Aspiring paleographers can also compare a variety of scripts, from Bastarda to Visigothic Minuscule.

In short, the Princeton Medieval Art index is another of the lesser-known research treasures the university has to offer. For more detailed research questions, the Index staff also takes research inquiries.

—Ignacio Arias, Humanities Correspondent