When I first walked into the lab this summer, I thought research was all about running experiments and gathering data. What I didn’t expect was how much the people around me—the mentorship and the shared triumphs and failures—would shape so much of my learning and how I view scientific research.

Starting a research position at a bioengineering lab over the summer was really intimidating for me, especially as an undergraduate. At the start, I felt like the most inexperienced person in a room full of graduate students, postdocs, and faculty who seem to have it all figured out. Although I’ve learned or at least seen a lot of the quantitative and qualitative components in my Chemical and Biological Engineering course, I did not have much hands-on experience and critical thinking that comes with actually doing experiments. That’s when I realized how big of a role a mentor plays.

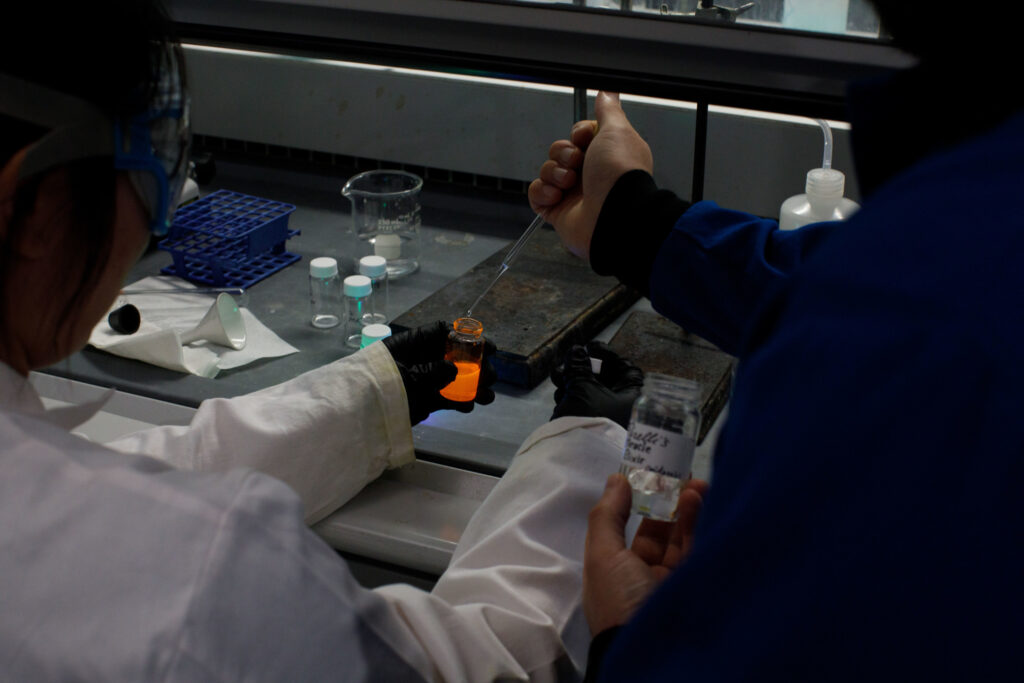

In the lab, I worked one-on-one with a Ph.D. student who showed me not just the technical sides of my project, but also the more nuanced, difficult-to-quantify skills needed to do research: creative problem-solving, knowing when to step away and reevaluate, and most importantly, persistence after failure. I worked on the development of a more sustainable protein purification method, which was quite a new, complex, and sometimes frustrating process that really had to be developed through trial and error. Never once did my mentor make me feel like failures over this were something shameful; instead, it was an opportunity to learn.

The thing that most impressed me about our mentoring relationship is just how much my mentor had invested in my growth as a person. Instead of giving me answers, they made me think for myself and solve problems on my own independently. When one experiment did not go right, instead of pointing out what was wrong, they simply told me to try a different route and asked me how I plan to go about navigating this shift. At first, this was daunting—I didn’t feel near confident enough to diagnose problems. Over time, though, I began to see value in this approach. I learned to map out different ways to approach a problem and ask the right questions.

Most importantly, my mentor taught me to trust myself and to be confident as a researcher. We would often have lunch together, and my mentor shared with me valuable advice on the wider academic journey at Princeton. Whether it involved helping me prepare for presentations or discussing career options in research and beyond, one was always ready to provide perspective. These conversations reminded me that mentorship isn’t just about the technical aspects—it’s also about personal growth and long-term development.

Having someone genuinely care about my goals both in and outside of research made all the difference. The lab in itself was a very collaborative working environment, and mentorship was not limited to one person. During lab meetings, everyone from an undergraduate to the postdocs had the ability to contribute ideas and give insights or critique one another’s work. It felt like we were all in this process of discovery together. If I ever felt really stuck, I could always count on someone to help me troubleshoot or brainstorm solutions.

The sense of community that this created – in the otherwise often isolating work of research – made it all feel even more connected.

The most important thing I learned in retrospect is that mentorship in research is not about teaching someone to do an experiment but essentially how to think. At Princeton, an undergraduate research experience is defined by the people who guide you, challenge you, and finally help you get more independent and capable as a scholar.

The most important step for any undergraduate looking forward to research is to find mentors who really care about your development. Do not be afraid to ask questions; even if sometimes that may mean admitting you simply don’t know the answers—those are the moments where you will learn the most. Strong mentorship will shape your experience with research, how you approach learning, problem-solving, and beyond. This lab experience has served for me both as a place of scientific discovery and one of personal development. I came in thinking that I would be taught how to run experiments, but I walked out with so much more: a deeper understanding of the research process, confidence in my abilities, and mentor relationships that continue to advise me as I navigate my academic and professional journey.

— Nathan Nguyen, Natural Sciences Correspondent