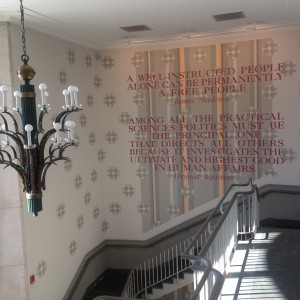

As you might remember from my first PCUR post, it can be incredibly rewarding to pursue research outside your comfort zone. If your time at Princeton doesn’t include at least one “just because” class, then you’re missing a few important experiences: first, the chance to expand your intellectual horizons; and second, the ability to navigate diverse styles of independent work. I’ve consciously tried to apply this idea by taking one class in a new department every semester. Yet after shopping six classes this spring, I settled on courses in History, African American studies, Politics, and the Woodrow Wilson School – four departments I’ve definitely been a student in before.

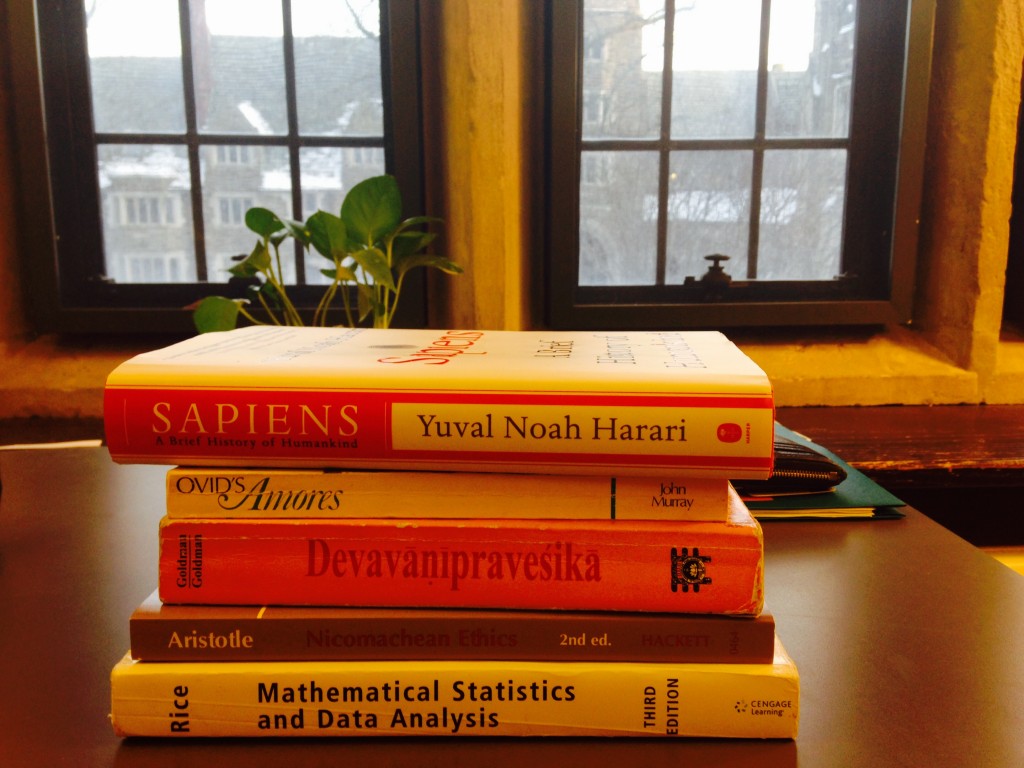

What happened? Well, it’s somewhat obvious: I chose the classes I expected to enjoy. It didn’t hurt that they were all related to, or required by, my major and certificate interests. It also didn’t hurt to read their syllabi and recognize texts and ideas from previous classes. In short, I felt comfortable with my schedule at the end of add/drop period… and it was a strange feeling. As Princeton students, we have access to so many amazing opportunities that it seems wrong to get comfortable in particular academic areas, rather than challenge ourselves in other ways.

I missed something important, though, by framing a conflict between comfortable and challenging classes: there’s no dichotomy between the two. Continue reading Don’t Be Afraid To Try Something Old