The summer after my first year, I worked for the Pringle Lab as an ecological research assistant in Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique. I have always loved the natural world, and my internship in Gorongosa allowed me to combine that love with my passion for scientific research. Camping for eight weeks amongst vervet monkeys, warthogs and baboons, and working with researchers in the savanna amidst antelopes, elephants, and lions made the internship a dream come true. That dream was made possible by the Princeton Environmental Institute.

Each year, PEI offers numerous established internships in locations around the world. These opportunities cover a range of environmental topics that address complex global issues related to energy and climate, sustainable development, health, conservation, and sustainability. All the internships last at least 8 weeks, are funded by PEI, and are mentored by a professional organization or Princeton professor. In addition to established internships, PEI also offers an opportunity to design your own internship with a professor if you are interested in a specific research topic.

My PEI internship provided me with real world experience in topics I was learning in classes and taught me how research works in the field.

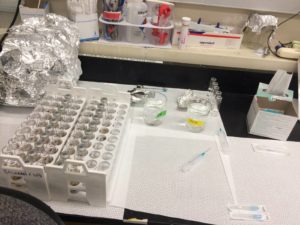

My PEI internship provided me with real world experience in topics I was learning in classes and taught me how research works in the field. I worked alongside three Princeton Ph.D. students, studying the diet of large mammalian herbivores, identifying trees on termite mounds, and surveying floodplain vegetation protected from herbivory with enclosures. Working with the small community of researchers in the park, I developed research skills such as how to plan field projects and take thorough field notes, while also strengthening my interpersonal skills. Much of our work related to the restoration of Gorongosa’s ecosystem following the ecologically catastrophic civil war in Mozambique, and I witnessed first-hand many of the issues that impact modern conservation and humanitarian efforts in developing countries.

If you likewise have a passion for environmentally related research, you can find detailed internship descriptions and application information on the PEI website. The final deadline for established internships is March 27th, but applications are considered on a rolling basis until positions are filled–so apply as soon as possible!

While it takes a little more effort to make a non-established internship happen, it really is all about taking initiative. My internship in Gorongosa was student-initiated and began simply with a couple of students asking Professor Pringle after class if we could intern with his lab. So if you are interested in creating a student-initiated internship, don’t be afraid to ask–talk to a professor or graduate student about creating an internship and get the ball rolling, and read about past internship projects to get ideas and understand what type of project will succeed. For advice on connecting with faculty members, see this recent PCUR post.

For students who are interested in summer research opportunities in non-environmental fields, the office of undergraduate research offers a student-initiated internship program over the summer called OURSIP. The priority deadline is March 1st, then applications are accepted on a rolling basis until April 1st.

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent