In the first article of this archival tour, I talked about the process of identifying the proper archives to further your research. But what happens next, once you have the archive, the collection, or the item you want? How do you proceed from there? For the purposes of this article, I will assume you are physically at the archive because we already have some great articles about requesting items from archives that you cannot physically be in. Here, then, I’ll talk about navigating the spaces of the archive and their uses, as well as some facts about archive etiquette.

Instead of dallying around, let’s jump back into the archive!

How do I get around the archive?

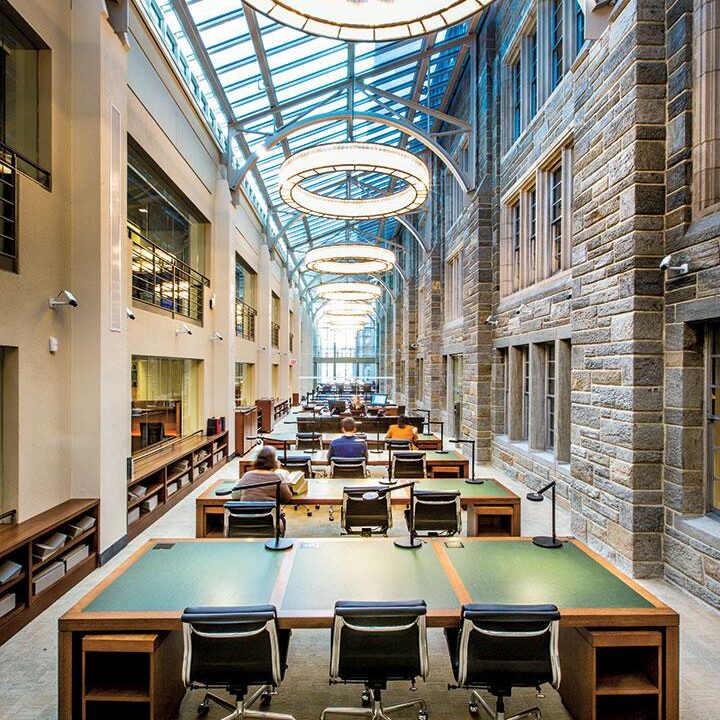

Most historical archives and a library’s special collections have a reading room. Usually, the only room you will be in is this reading room. This is the public-facing part of the archive, complete with rows of nice tables, some reference books, pretty art, some computers, and the librarians’ desks. There’s not much “getting around” to do, but I might as well quickly describe where to go and what to do.

My first stop is almost always the librarian. Usually, they can guide me to some of the collections I need (or requested in advance), as well as pull out those materials and give them to me. You never do the pulling yourself; you need the librarian for that. The librarian will also point you to some of the main rules of the library, too. For instance, at Detre Library, you’re not allowed to have your bag at the desk; you must leave it with the librarian.

Once you talk to the librarian, it’s time to find a good researching spot! There’s a bunch of different tables to pick from, so pick whichever feels right to you. There are no real criteria, but I normally like to be somewhat close to my materials if I have multiple boxes to sort through. While these are normally placed on wheeled carts for your convenience, I never found myself drifting too far away from the librarian. Maybe I liked the company?

The desk and tables are likely the two most important parts of the archive for a researcher. However, there are other places you should keep in mind. Often, you will see odd, rectangular computer screens next to weird-looking machines. These are typically used for reading microfilm, which is a way of storing sensitive historical material for a long period of time. If you have microfilm, you will be using these. Elsewhere in the library, you might see some bookcases. Normally, these are reference material: books about important, local families; print research guides and finding aides; some literature about the local region.

How do you behave in the archive?

While it would be a stretch to say that an archive has a specific type of etiquette, I think it might be worthwhile to point out some unspoken rules and norms of these institutions.

Once you enter the archive’s reading room, it’s worth remembering a very important thing: this is a library. Quiet prevails. While I would not say reading rooms are as quiet as Firestone, I would say it is best to respect the others around you and remain as quiet as possible. This includes not speaking loudly or often, as well as putting your phone on do not disturb, or not taking calls in the reading room. It’s best in the reading room to treat others as you would want to be treated.

The most important norm, however, is knowing when to ask to help. Unsure of how to use the microfilm reader? Ask the librarian. Can’t find the ideal collection for your research? Ask the librarian. Confused by the organization of a bankers’ box? Ask the librarian? And even if you are chronically shy, I would still ask the librarian. They’re typically incredibly nice and warm people who want to help you whenever, wherever! Even after I had left Detre Library to come back to Princeton after fall break, one of the librarians emailed me some digitized resources without me asking! Knowing when to ask for help, as well as building those ever-so-critical relationships with the librarians, is extremely important for the success of your research.

Given that we’re short on time and space, I’ll enumerate some other things archival researchers should keep in mind:

- Try to limit the number of boxes on your table to one. It might be hard to do this sometimes, but it helps you focus on this one box, as well as not jumbling up a bunch of records.

- Put things back into the order you found them. Pay specific attention to the folder numbers in boxes and make sure that you keep them in the order the archivist put them in. If anything seems out of order, ask.

- Request things clearly. Always stipulate what boxes you need (so they don’t bring you all of the boxes) to the librarian, preferably in writing or whatever request system the archive uses. For instance, at Detre, the librarian would also ask me to use one of the notecards at the desk and write down the collections that I needed.

- Never, ever, ever use pen when taking notes. Most archives actually mandate the use of pencils in their reading rooms, because getting pen on hard-to-reproduce documents would compromise their integrity and make life a lot harder for the hard-working librarians.

- Never annotate the documents themselves. Bring a notebook, computer, or another device with you to take your notes, as most archives allow it.

- Pictures are normally allowed. Typically, you are allowed to take pictures of items with your phone or a camera of documents and materials. Often, too, you can request items to be scanned, but this might have a cost. Do keep in mind the archive’s policies; some items might be somewhat more sensitive or the archive itself might have specialized rules, which leads us to the final and most important tip:

- Always consult the rules the archive lays out to its users. If you are ever unsure about anything, this might be a good place to start. For instance, you can find Princeton Special Collection’s guidelines here.

This information should be invaluable to a new user of an archive so that you don’t unknowingly damage sensitive historical material, become confused by the weird computer screens, or know who to ask for help. However, you’re probably still curious about one last part: How do I do research in the archive? What tools do I need? How do I make sense of the documents? These are perhaps some of the most important questions, and answering them will require time, thought, and many words. Thus, please check out the final part of this series: researching in the archive!

– Austin Davis, Humanities Correspondent