In my junior year of high school, through my conversations with more and more teachers and scholars, I thought I had come to understand the importance of one inevitable piece of the scientific process (or really any academic discipline):

Failure.

If science was the first name, failure would be its last name; its defining characteristic; its essence. My understanding was that successful scientists embrace failure. I thought they impatiently wait for failure to happen and they are so immune to it that failing does not bother them.

Then, the summer before senior year of high school, I joined a lab at the Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. It was my first time in a real lab setting, and the first time I experienced scientific research first-hand. That summer, most of my experiments failed. It was challenging to get the apparatus to work, and placing all the knowledge that I had learned directly into experiments just seemed impossible.

After the fifth experiment failed, I was convinced that the beauty of failure was only in words. I had not experienced until that moment what failing truly meant. And now that I had experienced failure, I did not want to go near it anymore. It simply felt devastating. Failure – which I thought of once as the holy grail of science – was not beautiful, nor was it valuable anymore. The beauty had become the beast!

And thus, I had learned to fear failure … until this summer.

I was at Harvard this summer, at the laboratory of Professor Jennifer A. Lewis. For 10 weeks, I worked on developing techniques for 3D-bioprinting organs. I learned A LOT, even without failing. Every experiment was going perfectly, minute-by-minute.

Then came a hot day in the middle of July (like HOT HOT. Boston in the summer is perfect for melting!) I had created some agarose microparticles – which are very small polysaccharide particles – that we were planning to use as the ink for the print. One important characteristic of these microparticles is their ability to bind DNA. Therefore, I wanted to compare the binding ability of agarose microparticles with gelatin ones.

I decided to get creative. I had encountered gel electrophoresis in MOL214. In this technique, DNA is separated by size by running a sample through a porous agarose gel with an electrical charge. So I hypothesized that DNA could move in the agarose gel, indicating that the gel is not restricting its movement. Running 2 gels, one made of agarose and the other made of gelatin, would give me some reliable data.

I made the 2 gel solutions and ran the agarose gel first, which went perfectly, giving me information about the affinity of agarose for DNA.

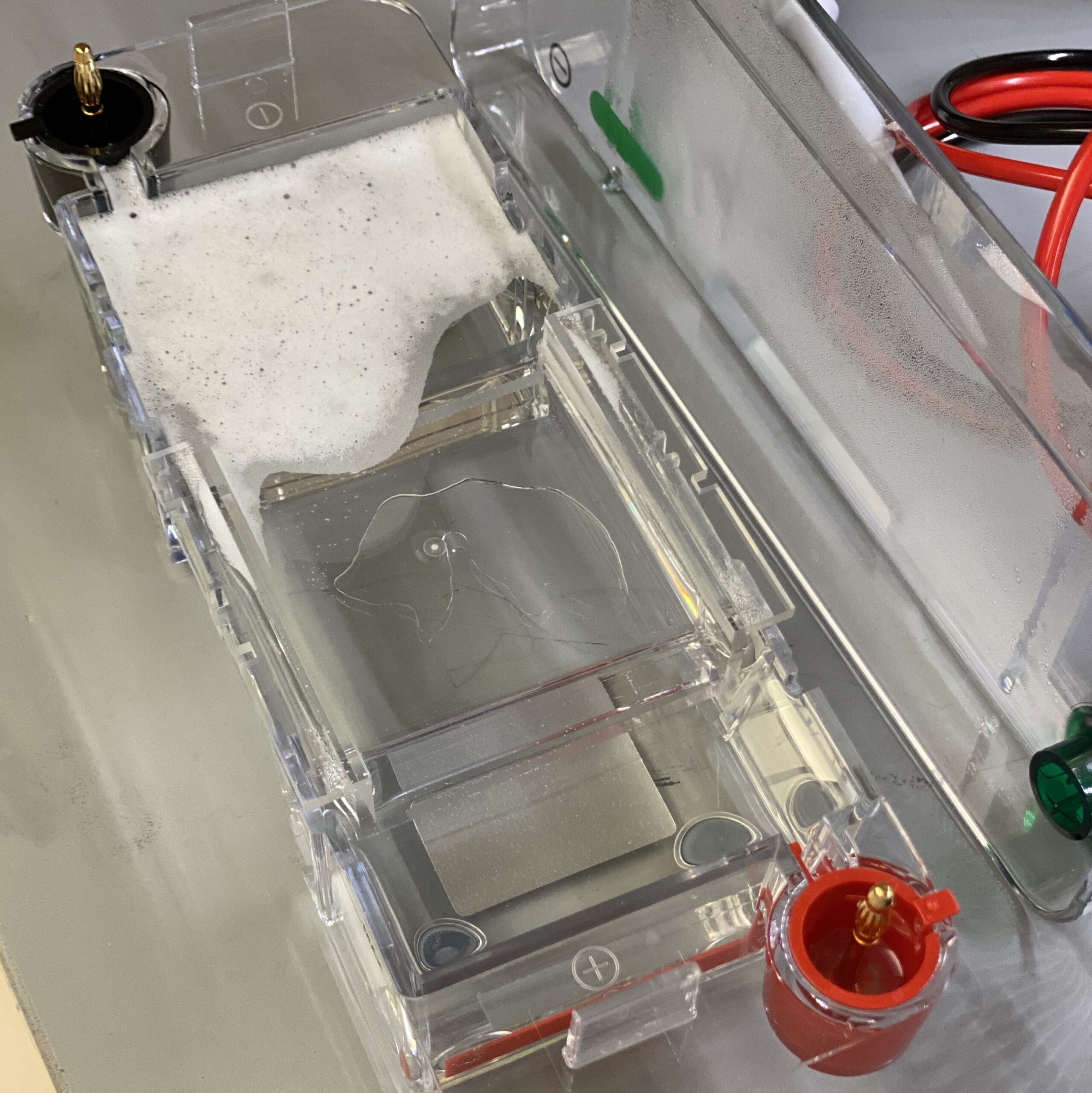

Then it was gelatin’s turn. I thought I had done everything right. I made the gel solution, loaded it into the apparatus, and set the gel to run at 5 volts/centimeter for 30 minutes. I came back half an hour later. And I saw the most shocking result I’ve encountered in science so far: the gelatin had melted.

A failure.

What is interesting is that after the shocking moment passed, I felt an adrenaline rush in my body. I was surprised to see the gel melt, but it was a good surprise. Yes, I wished I had just thought about the fact that the electric current produces heat before running my experiment (and frankly I did wish I had spent more time in the kitchen making Jell-O!). But this experience motivated me to learn more about the chemical properties of reagents in the laboratory. I also gained an insight into how, in designing an experiment, it is important to think beyond just the method being used and also take into account the materials used.

It was also then that my mentor in the lab told me a key sentence that I still carry with me today, “That is why what we do is called REsearch. We search for answers; we fail, and then we redo it. Otherwise, we would be called searchers and not researchers!”

Among all the wonderful scientific facts that I learned this summer, I think my most important learning was to embrace failure, but not because it comes with a great feeling. It is hard, and it can be discouraging. But it also comes with empowerment, achievement, and glory. Failure is not a beauty, nor is it a beast. It is both at the same time, and that is what makes it unique.

So here is a frank message from a sophomore college student:

Fail. And fail beautifully. Then learn. And apply what you learned beautifully!

— Mahya Fazel-Zarandi, Natural Sciences Correspondent