Robert P. George is McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and the founder and director of the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions. His courses, Civil Liberties and Constitutional Interpretation, have long been famed, loved, and sometimes feared by students for their intellectual rigor and exact grading. Over the course of his 40 years of teaching at Princeton, he has mentored and inspired scores of students. For our seasonal series on mentorship, I asked Professor George about his experience both as a mentor and a mentee.

Continue reading “The Luckiest Man in the World”: An Interview with Professor Robert P. GeorgeReading Courses: A Guide

As course selection begins, you might find yourself searching endlessly through the Course Offerings webpage, trying to craft the perfect schedule for next semester. You’re probably weighing a number of different factors— the professor, the class topic, the reading list, the different requirements it fulfills— and trying to balance these in the best way possible.There is another possibility here, which you can’t find in the course offerings: reading courses. Not advertised on department websites or listed with course offerings, reading courses are some of Princeton’s hidden academic gems. The University defines a reading course as a specially designed course not normally offered as part of the curriculum that is arranged between a student and a faculty member. These courses count for academic credit, and focus on a topic of the student’s choosing. If you’ve ever dreamed about designing your own course, this is your opportunity.

McCosh Courtyard in November

Continue reading Reading Courses: A GuideLearning a Language Off-Campus

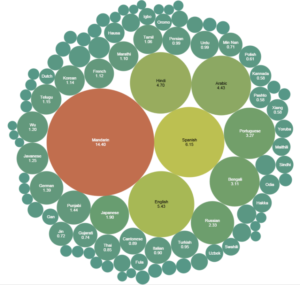

According to its website, Princeton offers courses in about twenty modern languages. Sounds pretty comprehensive – until you consider that the world has literally thousands of distinct living languages.

As I start preparing for my independent work next year, I’m thinking a lot about language ability, especially as it relates to primary source access. For non-Anglophone historical research, facility in the region’s language/s is essential to original scholarship. Personally, I’m interested in Eastern European Jewish history. The good news: I only really need one language to study primary sources from this period. The bad news: it’s not one of the twenty offered on campus.

A Reading Course with Local Impact: Analyzing Ecology on Campus

In my last post, I wrote about finding meaning in my academics through a research oriented class with local impact. This week, I am focusing on how another student is using research to make a positive local impact–not through taking a pre-existing course–but by creating a reading course that fit her specific academic goals. (If you are interested in reading courses, you can learn more about them here!)

This fall, Geosciences major Artemis Eyster ’19 is leading GEO 90_F2017 “Analyzing Ecological Integrity: An Assessment of Princeton’s Natural Areas,” a course she designed that centers around geological and ecological field research on Princeton’s campus. The eight students enrolled in Analyzing Ecological Integrity (AEI) are tackling field research projects such as measuring the bathymetry of Lake Carnegie to assess the rate of erosion on campus lands, gauging water-quality in campus streams, and surveying invasive plant species in campus woodlands. Artemis leads weekly class meetings to discuss course goals, review progress, and plan ahead, with the assistance of course advisers GEO Professor Adam Maloof and WRI Professor Amanda Irwin-Wilkins. I interviewed Artemis to better understand her motivation for creating the course and her experience taking charge of her academic work to make a positive impact on our campus.

What do you consider to be the purpose of this reading course?

AEI is about better understanding Princeton’s natural areas through rigorous scientific research and using our findings to articulate relevant land-use recommendations to the University. I believe that, as students going here, we should take responsibility for the land and environment around us. If we have the ability, we should use our scientific skills to help the University make decisions that protect our campus’s ecology. Another priority of the class is to record baseline measurements and design methodologies so that future student researchers have a strong framework they can expand upon either in classes or independent work.

“It is empowering to be able to identify something that I think is important and then go make it happen.”

How did you develop the idea for this reading course?

[GEO Professor] Adam [Maloof] saw a natural resource assessment report provided to the University by a professional consultant and thought that students could advance such assessments with high quality scientific measurements and greatly expand upon the work currently being done by the University. I love fieldwork, and I thought other students would also be excited to do impactful research on campus. Creating the class was a way to harness that excitement into commitment so that we would be able to get research done over the course of the semester.

Continue reading A Reading Course with Local Impact: Analyzing Ecology on Campus