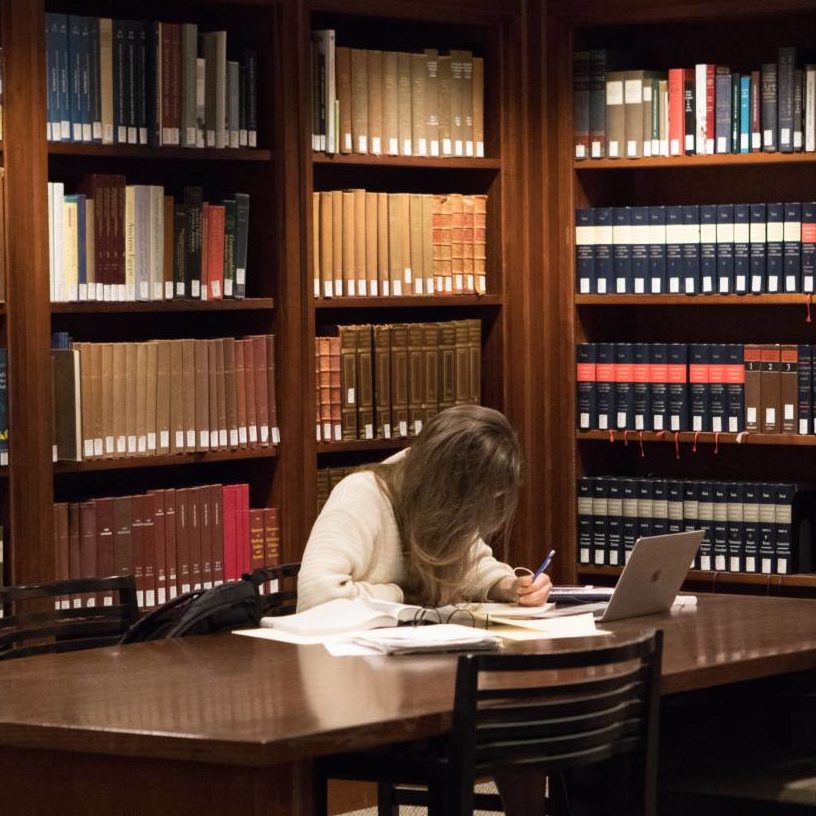

At some point in your Princeton career, you will likely have to write a long paper replete with a table of contents and extensive bibliography, possibly containing complex mathematical equations, and/or multiple figures and tables. For many students, especially those in the social sciences or humanities, writing a research paper using word processing software like Microsoft Word will be the fastest and most intuitive method (especially with the help of automated citation tools). However, for other students, formatting all of these features using regular word processors will be inefficient, or worse, create unsatisfactory results.

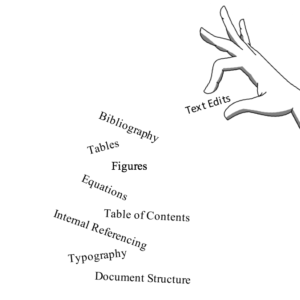

For these types of projects, you may benefit from a typesetting system capable of consistent structural layout, superior typographical quality, support for scientific equations, internally referencing figures and tables, and automatically compiling large bibliographies. Enter: LaTeX.

LaTeX is a free open-source typesetting system that uses code and text to generate a PDF document. It allows you to explicitly define formatting options so that document structure remains consistent. Although the workflow is completely inefficient for writing short documents, when it comes to large and complex papers, LaTeX can make life a lot easier. For projects like Senior Theses, many departments at Princeton even have LaTeX templates with correct formatting built-in. While struggling to get a handle on LaTeX last year, I learned some useful strategies that will help you vault over the learning curve: