Many of us might think of classwork and research as two separate entities. Here at Princeton, we might think, we take classes to learn and to prepare ourselves for independent work, but the two are distinct concepts. But reality is, of course, much more complex: classes at Princeton can and do incorporate elements of independent research work. This spring break, I had the opportunity to conduct field research as part of one of my classes, GEO 372 (Rocks!). We flew down to Death Valley National Park for a week, collecting various rock samples and learning about the regional geology. For the rest of the semester, we’ll be analyzing the samples to answer our given research question.

Continue reading Classwork Meets Research Work: A Unique Field-Based Experience in Death ValleyThe Art of Cartography: Creating Maps for your Research

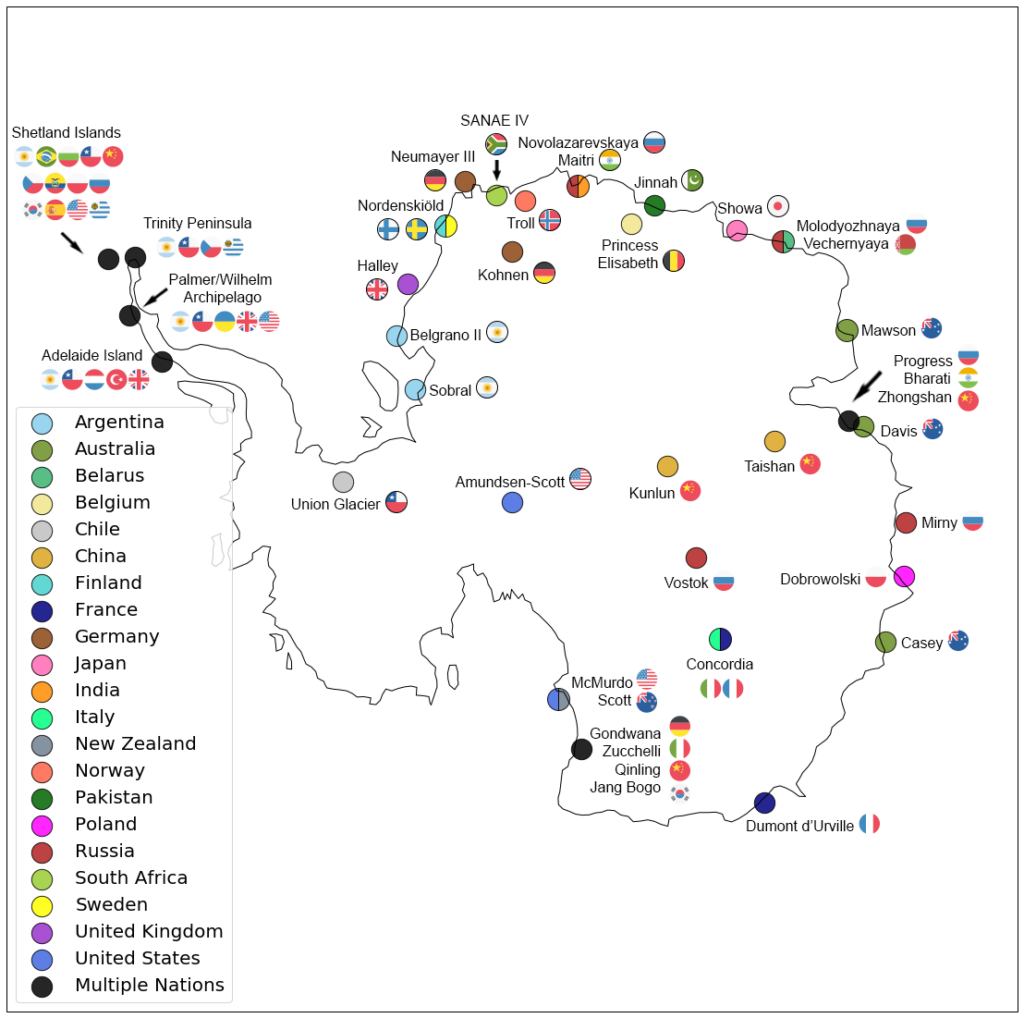

Ever since I was a child, I’ve always loved maps—I was a major geography nerd growing up. Jumping forward to today, my like-minded roommates are just as obsessed as I am: the walls of our dorm are literally covered floor to ceiling with maps. These include (but are not limited to) a glaciological map of Antarctica, public transport maps of numerous cities (Toulouse, Christchurch, and New York are just some examples), and a road map of my home state of Washington!

Maps aren’t just a fun hobby: They’re also enormously important in numerous research fields (in addition, of course, to just being plain useful). Whether your research field of interest is history or meteorology or epidemiology, there’s a good chance that you’ll be reading—and making!—some maps. In my own field of glaciology, maps are of paramount importance, whether it’s a map of glacier melt contribution from southeast Alaska or a map of Antarctic ice core sites. I’ve written this guide to provide some helpful resources and tools for making maps for your research, so hopefully it will serve as a good starting point! I should note that this isn’t a tutorial, but plenty of great tutorials should exist on the Internet for all of these tools.

Continue reading The Art of Cartography: Creating Maps for your ResearchCitations, Citations, Citations: A Guide to Keeping Track of these Pesky Beasts

If I have to be completely honest, dealing with citations is my least favorite portion of the academic writing process. Ascertaining what citation style I need to use, successfully figuring out how to actually format citations in that style, and managing the hodgepodge of footnotes and endnotes are all tasks that seem, to me, cumbersome. Of course, these are necessary tasks: it is imperative that if we paraphrase, quote, or utilize in any way the work of others, we should always attribute the proper credit to them. But recognizing the importance of academic integrity doesn’t prevent us from still finding the task of dealing with citations to be a chore! If you’re in the same boat as I am, I’ll try to provide some advice and tips on dealing with citations!

Continue reading Citations, Citations, Citations: A Guide to Keeping Track of these Pesky BeastsDemystifying Big Data: An Introduction to Some Useful Data Operation Tools

“Big data” and “data science” are some of the buzzwords of our era, perhaps second only to “machine learning” or “artificial intelligence.” In our globalized, Internet-ized society of plentiful information galore, data has become perhaps the most important commodity of all. Across all kinds of academic disciplines, working with large amounts of data has become a necessity: universities and corporations advertise positions for “data scientists,” and media outlets warn ominously of the privacy risks associated with the rise of “big data.”

This isn’t an article that discusses the broader, societal implications of “big data,” although I highly encourage all readers to learn more about this important topic. Instead, I’m here purely to provide you some (hopefully) broadly applicable tips to working with large amounts of data in any academic context.

In my own field of climate science, data is paramount: researchers work with gigantic databases and arrays containing millions of elements (e.g., how different climate variables, such as temperature or precipitation, change over both space and time). But data, and opportunities for working with data, are present in every field, from operations research to history. Below is an overview of some existing data operation tools that can hopefully assist you on your budding data science career!

Continue reading Demystifying Big Data: An Introduction to Some Useful Data Operation ToolsPresenting at Academic Conferences: Tips and Tricks

The author presenting at the American Geophysical Union 2023 Fall Meeting.

Imagine the following scenario: after months of committed, in-depth research on the academic topic of your choice, you’ve finally obtained some pretty cool and novel results. Your adviser is excited, and their reaction is enthusiastic—“Hey, what if we submit an abstract to an academic conference?” This was the situation I found myself in last year, when my advisers suggested I present my research on reconstructing past Antarctic snowfall patterns at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco. I felt honored and excited, but also a bit nervous. How was I, a lowly undergraduate, going to present my work to a massive academic conference the size of a midsized town?

Luckily, I was fortunate enough to receive a lot of great advice from mentors and peers, and in the end it turned out great! Now, I’ll try and share some of that advice with you all—I hope you’ll find it useful!

Continue reading Presenting at Academic Conferences: Tips and TricksDiving into the “Scholarly Conversation” and Other Tips on Academic Writing

Every student at Princeton lives their own unique experience, but if there’s one thing all Princeton students have in common, it’s that we all need to know how to write academically. The only required class for all Princeton students, first-year writing seminar, is a rite of passage. Later on, students of nearly every single major must complete independent work, writing their junior papers and senior theses; when writing these, knowing how to effectively communicate your findings is an essential skill. Here, I’ll talk about some strategies for getting a handle on academic writing, which I hope you’ll find useful!

Continue reading Diving into the “Scholarly Conversation” and Other Tips on Academic WritingField Research on the Juneau Icefield: Living the Emersonian Triangle

Students across a variety of disciplines (or fields, if you will) have the opportunity to perform fieldwork at Princeton. In contrast to lab work—which involves performing experiments or analyses within a controlled on-campus environment—fieldwork takes place, well, in the field. Researchers venture out into the wide, wild world in pursuit of somehow collecting useful data from the vast webs of chaos that surround them. In my home department of the Geosciences, fieldwork is the norm: students go out to geological field camps or embark on oceanographic cruises to gather data about the raw Earth that surrounds us. However, fieldwork is truly possible in any discipline.

This past summer, I conducted my own fieldwork as part of the Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP). For two months, I lived and conducted glaciology research with about 40 other students, staff, and faculty on the glaciers of the Juneau Icefield—an interconnected system of over 140 glaciers spanning 1500 square miles across southern Alaska and northern Canada. It was one of the most incredible—and intellectually rewarding—experiences of my life. Here, I’ll share some stories from my time on the Icefield, contextualizing them within some broader lessons I learned about how field research operates.

Continue reading Field Research on the Juneau Icefield: Living the Emersonian TriangleSurf’s Up: A Guide to Internet Surfing, and other Assorted Browsing Research Skills

If you’re anything like me, you first thought that “research” essentially amounted to surfing the Internet. Back in the glory days of middle school, “research” meant the rewarded privilege of getting to use the laptop carts, productively using class time on googling information about our various project topics (and definitely not secretly playing games). Now, as the mature, worldly college student you now are, perhaps you think you know better. “True” academic research, the clever reader now knowingly tells themselves, is historians dusting through archival documents and scientists mixing frothy chemicals in the lab.

Yet there’s a missing part here: a crucial element that takes us back to our elementary and middle days of excited googling. To make any significant intellectual contribution to any field, one first has to understand the current state of knowledge in that same field. To borrow the term favored by the Writing Program, we need to understand the scholarly conversation. How do we know if we’re making a contribution to something, if we don’t understand what that something is? Understanding the current state of research in a given field is a crucially important skill—really, a prerequisite—for conducting your own effective research in that field.

Continue reading Surf’s Up: A Guide to Internet Surfing, and other Assorted Browsing Research Skills