I think mentorship can be highly overlooked in the undergraduate community. This is mostly because we feel that professors and Ph.D. students can be so far in their own fields, and so we’re just intruding in on their time. They’re so impressive that it is almost intimidating. However, in hindsight, you start to realize how important their mentorship becomes in your life. I think a lot of undergraduates value mentorship in the sense that they’re being given an opportunity in the current moment to do research or work on a project. This is the perspective I had on mentorship when I entered research. Luckily, for me, mentorship turned out to be so much more; it’s the gift that keeps on giving.

Continue reading The Beauty of MentorshipHeads Up: You Might Need Study Approval from the Institutional Review Board

Independent research at Princeton offers an incredible opportunity for students to explore their academic interests and gain experience in the research world. This year, I’m working on my Senior Thesis with Professor Aleksandra Korolova, conducting an audit of Google ad delivery optimization algorithms. Specifically, I am studying whether aspects of advertisements—the image, text, links, and so on—impact the demographics of the audience to whom the advertisement is delivered.

In the fall, many people were curious about how my thesis was progressing. The truth was, for a few weeks, I hadn’t started running any experiments, since I first needed my research to be approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Through this experience, I both gained insight into the IRB process and found that many students had never even heard of the IRB. In this article, I share my experience and offer advice for students who are planning to conduct independent research.

Continue reading Heads Up: You Might Need Study Approval from the Institutional Review BoardResearch is Better with the Right Mentor—How I Found Mine

When I first came to Princeton, already interested in neuroscience research, I kept hearing about all the incredible opportunities available to undergraduates. Professors conducting groundbreaking neuroscience studies, cutting-edge labs filled with brilliant minds—it all sounded amazing. But as a first-year student, I had no idea how to actually get involved. Everyone seemed to know what they were doing, while I was stuck wondering: Where do I even start? Will a professor really take time to mentor someone like me? If I cold-email them, will they even read it?

Continue reading Research is Better with the Right Mentor—How I Found MineStaying Connected

Each spring semester, it feels like many of us find ourselves scrambling to find unique, competitive, and exciting research experiences. In these intense weeks full of interviews, rejections, and offers, it is also important to think ahead about what comes next. Although staying connected with your research team after a program or internship ends can present a unique set of challenges, it can just as easily open up a number of new opportunities. This was a dynamic I had to adjust to at the end of my research internship last summer. Through that personal experience, I have found that consistent and clear communication are key after any research experience.

Continue reading Staying ConnectedThe Art of Cartography: Creating Maps for your Research

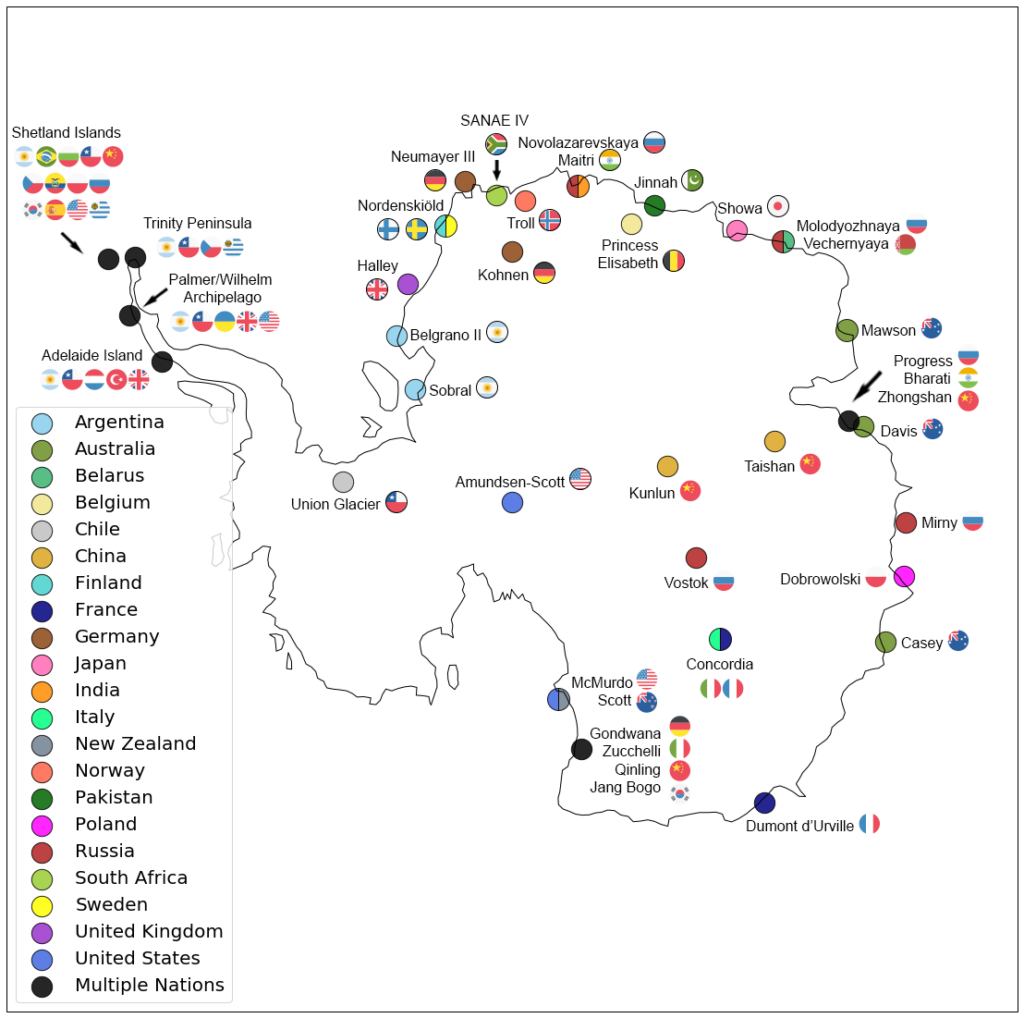

Ever since I was a child, I’ve always loved maps—I was a major geography nerd growing up. Jumping forward to today, my like-minded roommates are just as obsessed as I am: the walls of our dorm are literally covered floor to ceiling with maps. These include (but are not limited to) a glaciological map of Antarctica, public transport maps of numerous cities (Toulouse, Christchurch, and New York are just some examples), and a road map of my home state of Washington!

Maps aren’t just a fun hobby: They’re also enormously important in numerous research fields (in addition, of course, to just being plain useful). Whether your research field of interest is history or meteorology or epidemiology, there’s a good chance that you’ll be reading—and making!—some maps. In my own field of glaciology, maps are of paramount importance, whether it’s a map of glacier melt contribution from southeast Alaska or a map of Antarctic ice core sites. I’ve written this guide to provide some helpful resources and tools for making maps for your research, so hopefully it will serve as a good starting point! I should note that this isn’t a tutorial, but plenty of great tutorials should exist on the Internet for all of these tools.

Continue reading The Art of Cartography: Creating Maps for your ResearchComputer Science Independent Research: A Conversation with Anna Calveri ‘26

The senior thesis is a hallmark of the Princeton experience, giving students the opportunity to conduct original research under the mentorship of a faculty adviser. Every senior is required to write a thesis, with the exception of Computer Science majors in the Bachelor of Science in Engineering (B.S.E.) degree program. Instead, these students are required to undertake a substantial independent project, called independent work (IW), which can take the form of a traditional one-on-one project with an adviser, an IW seminar where a small group of students independently conduct projects tied to the seminar’s main theme, or an optional senior thesis.

In 2022, I interviewed Shannon Heh ’23 about her experience in an IW seminar, where she highlighted the structure and guidance the professor and course seminar. This year, I wanted to explore the perspective of a B.S.E. Computer Science student who pursued a different option: the one-on-one IW project.

Anna Calveri ’26 stood out as the perfect person to speak with, not just because of her exciting research at the Princeton Vision & Learning Lab led by Professor Jia Deng, but also because she began her project during the summer as a ReMatch+ intern and built on it during the fall semester. While many students only work on their IW within a single semester, Anna’s approach of extending her research across both the summer and fall gave her the chance to deepen her research and hit the ground running with impressive progress.

Continue reading Computer Science Independent Research: A Conversation with Anna Calveri ‘26Looking Ahead to Spring (And Summer)

For Princeton students, it’s not premature to start thinking about summer. If anything, this post may be a little behind for some of those proactive students. Rest assured though, you are not behind if you have not started the search for summer internships (even though many students will say they’ve already applied). Opportunities are aplenty, and no, you are not behind if you didn’t start applying for research internships back in the womb.

Continue reading Looking Ahead to Spring (And Summer)Demystifying Big Data: An Introduction to Some Useful Data Operation Tools

“Big data” and “data science” are some of the buzzwords of our era, perhaps second only to “machine learning” or “artificial intelligence.” In our globalized, Internet-ized society of plentiful information galore, data has become perhaps the most important commodity of all. Across all kinds of academic disciplines, working with large amounts of data has become a necessity: universities and corporations advertise positions for “data scientists,” and media outlets warn ominously of the privacy risks associated with the rise of “big data.”

This isn’t an article that discusses the broader, societal implications of “big data,” although I highly encourage all readers to learn more about this important topic. Instead, I’m here purely to provide you some (hopefully) broadly applicable tips to working with large amounts of data in any academic context.

In my own field of climate science, data is paramount: researchers work with gigantic databases and arrays containing millions of elements (e.g., how different climate variables, such as temperature or precipitation, change over both space and time). But data, and opportunities for working with data, are present in every field, from operations research to history. Below is an overview of some existing data operation tools that can hopefully assist you on your budding data science career!

Continue reading Demystifying Big Data: An Introduction to Some Useful Data Operation ToolsA Guide to Poster-Making

You’ve finished a research project and now you’re on to the final step: presenting your work! It’s time to share the incredible work you’ve done with the general public, and one of the best ways to do so is to create a poster conveying the significance and conclusions of your research. This will be an essential skill during your time at Princeton whether for a course or as a part of your junior and senior independent work. If this is your first time creating a poster presentation, check this blog out!

The Skills for the Job

Research is always top of mind here. Princeton is a research university. Princeton faculty are engaged in research. Princeton students complete independent research to graduate. These are just some of the ways that we collectively understand what research is as Princeton. Yet, the images that can come to mind when thinking about “research” are quite limited. The idea of research conjures up images of bubbling chemicals and expensive technical equipment. That picture of grueling lab work is illustrative of some disciplines, but it’s largely immaterial to the work of many researchers. This can lead to a misunderstanding of what skills are necessary to succeed in research environments. Getting involved with research is daunting enough without confusion about the skill set required. This past summer, when I worked in public health research, I identified core skills that are critical, no matter what your research experience looks like.

Continue reading The Skills for the Job